ADDENDUM TO STORY OF NACERE JOSE ARTIGA ESCOBAR

Esta historia se escribe en Español = This story is also written in Spanish here.

Editor’s Note: We ran Jose’s full story in June, 2015. If you are new to our website and did not read it, you can access it by typing in “Jose Artiga” under the search stories box on our main page. Jose recently added his full Spanish translation of his story.

In addition Jose shares this frightening event which happened to him during the Civil War. The Eileen he refers to who came to his rescue is none other than his partner, Eileen Purcell, who moved heaven and earth to rescue him from thousands of miles away.

The Capture of José October, 1989

We had entered El Salvador with the fourth repatriation of the 20,000 refugees of Mesa Grande, Honduras, which occurred in the last week of October, 1989. We spread out between the different repatriated communities. In the three previous repatriations the Going Home delegations had not been allowed to enter. Ron Morgan, Bob Perillo, and I went with the people of Corral de Piedra, known today as Ellacuria in honor of the assassinated Rector of the Central American University UCA, and the Jesuit Father, Larry Castañola; Nicolás Avelar went with the people of Tremedal, and so on. After leaving the people, we were invited to go to Arcatao to take testimony of the army’s repression against the civil population.

We knew we were in danger, so to camouflage our departure from the area, the ‘Directiva’ (City Council) arranged to get us out in the midst of a large group of people leaving in a truck.

The military road block was waiting for us, and at the checkpoint they captured Ron and Bob because they stood out from the rest of group. As a Salvadoran and a ‘chele’ (lighter-skinned) like the Chalatecos, the guards did not discover me. However, I gave myself up to accompany Ron and Bob, who did not speak Spanish and who were a part of our group in the Going Home delegation.

The soldiers let the truck pass with the people but took us to the Chalatenango police barracks. “Maria,” a woman who came in our truck, followed us to the barracks at a distance and waited among a group of people across the street to accompany us.

Maria Chilchilco

They “detained” us in the plaza of the barracks without letting us move. Suddenly a boy from the truck approached us selling a newspaper. Whispering, he told me to act as if I were reading the paper and to write down the phone number of whom they should call. I wrote down the phone number of the SHARE Foundation in Washington D.C., (202) 319-5540, and the boy took the paper to the convent where the people of the community were mobilizing for our freedom. They called Eileen Purcell and explained that we had been captured. Given the conditions of the repression of those who were captured, and were often disappeared, it was urgent.

“Maria,” who risked her own life by looking after us, was still in front of the plaza hidden between the vendors. I looked for her and saw only her brown eyes. They detained us in the plaza of the barracks for several hours. Eileen started a strong national campaign and mobilized earth and sky to demand our freedom; she reached all the way to the State Department. We were resisting that they move us to the Fourth Brigade because it was infamous for disappearing those who they captured and for killing them. We demanded that they allow us to call the United States embassy to leave a record of our capture. By the afternoon we were tired and hungry. Three advisors from the US Army arrived and allowed us to make the call to the embassy. They proceeded to move us quickly to San Salvador putting us in an armored military vehicle. Ron and Bob were in the armored part while I was in the uncovered part. The soldiers said that there was the risk of an ambush, in which case I would surely die. When we pulled away from the plaza, I could see that Maria, who had accompanied us all day, left the crowd of people where she had been hiding and gave me a sign of encouragement with a white handkerchief.

UCA Chapel, Martyrs

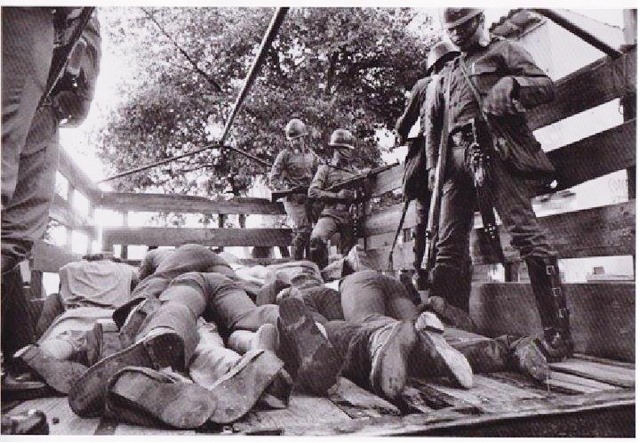

That night we arrived at what we discovered later was the general barracks of the Treasury Police (Policia de Hacienda PH), which was notorious because they never took prisoners. Later on, many graves would be discovered on the grounds of the barracks. They took a very long time to process us. The phone in the office rang and rang without stopping, and the police stood without answering it. They were the thousands of calls that Eileen was mobilizing. This gave us hope. Then they took our tapes of the testimony of Arcatao. We then got into a vehicle that drove us around aimlessly. The soldier made a comment saying, “Finally they gave the order to kill these terrorists.” Ron asked me to translate what the soldier had said, but instead I told him that the soldier had said that they were taking us to a place where we could rest. I knew the reputation of the PH to never take prisoners. They had assassinated Monseñor Romero, the four US sisters; they were responsible for thousands of political disappeared, and two weeks later they would assassinate Elba, Celina, and the six Jesuits in the Catholic University of Central America UCA. The possibility that they would kill us was very great.

Maria Julia Hernandez

The vehicle drove on for a long while going around and around before we finally arrived at our destination. We later found out it was the same Policia de Hacienda where we had arrived initially. It was hard to walk without tripping and falling because we were blindfolded and our hands were tied behind our backs. They separated us and put me in a cell by myself. They ordered me to take off all my clothes, shoes, absolutely everything. They put the blindfold back over my eyes and handcuffed me again. There was a guard who ordered me to stand in the middle of the cell under a dim light. The cell smelled bad and there was a sound of water that would not stop. It was very difficult to stay awake, standing and hungry. When completely naked, one feels very vulnerable and defenseless. It was going to be the longest night of my life. I began to remember every year of my life up to the moment of my capture. I didn’t have time to say goodbye to my sons, Alejandro (7 months old), Tilo (2 years old), and Camilo (5 years old), or to Eileen, or to my family in El Salvador, just like the ten thousand disappeared who to date have not been found and whose mothers still look for them. I had lived nine years, five months and three days since the death squad arrived at my home in San Martin with orders to kill me on June 27, 1980, at 10pm. My thoughts were interrupted by the sound of the door opening and the screams of people being tortured in other cells. They wanted to know who gave me my orders, who the guerrilla contacts in the U.S. What were the names of our contacts in the churches in El Salvador? Who were the leaders? What were their plans? What are the targets they are going to hit in the offensive? The repatriation came on the eve of the great offensive of November 10.

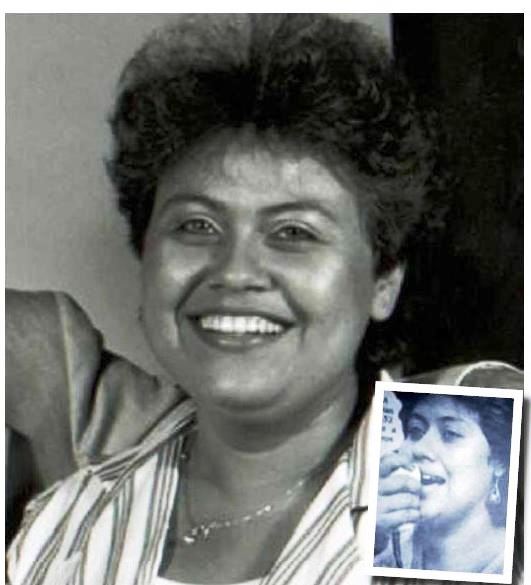

Eileen Marie Purcell photographed in a more casual moment.

The next day they removed me from the cell and took me to room where Ron and Bob were. Our good friend Maria Julia Hernandez from the office of Tutela Legal of the Archbishop of San Salvador came to take our testimony. This was a huge victory secured by Eileen and the national pressure campaign for our release. If they recognized us as being captured, we had hope to live.

With the unrelenting pressure the US Embassy finally intervened on behalf of Ron and Bob but refused to do so on my behalf, even though I was a US resident. Thanks to my brothers Ron and Bob, who said that we are three and not two and that they refused to leave me behind in the prison, I was not abandoned.

After hours of waiting and of more pressure, they informed me that I was to be freed. They brought me my clothes and ordered me to get dressed quickly. I tried to hide the blindfold in my shoe to have proof of how we were treated, but they ordered me to give it up or I wouldn’t be able to leave. They gave us a long document which said that they hadn’t mistreated us and which exonerated them from all liability. I carefully translated the document, first to Ron and then to Bob, to waste time. We demanded that they return the tapes they had confiscated from us. They went to look for them but, of course, could not find them. I asked Ron and Bob if they would agree to delay our release to give more time for our friends in the US to organize the protests I was sure they were planning. They looked at me incredulously. Eventually the lieutenant told us that if we kept delaying, he’d put us back in the cells.

Still “detained,” we were handed over to the staff of the US Embassy. The embassy staff took us to their office where they put us on the phone with Eileen. With them listening on the same line, we told Eileen that we were free and she could now stop the campaign to pressure the embassy.

That day they took us to the Hotel Alameda with orders to not leave. They put two police officers outside our door to make sure we remained detained. In the hotel we met a delegation of the SHARE Foundation from Detroit, MI, including Bishop Tom Gumbleton, Sister Sue Sattler, IHM, and Bill and Mary Carry, all of whom had been pressuring the “Estado Mayor” in San Salvador for our freedom.

Feve Elizabeth Velasquez

That evening was the burial of the nine trade unionists killed by a bomb placed by the Death Squad in the FENESTRAS offices. Among those who had been killed was Feve Elizabeth Velasquez, its general secretary. In order to leave the hotel and attend the funeral, we made a plan with the cooks of the hotel. They brought a big plate of food for the police and got us out the service door of the hotel without the police realizing. The funeral was a massive event which was both combative and full of protest, much like the Popular Revolutionary Bloc of the 1970s in El Salvador and the African National Congress of South Africa. Carrying the coffin of Feve Velasquez filled me with commitment and determination to return to the U.S. to work day and night to help stop the military intervention of the U.S. and to end the war. I remember the electricity in the environment when we shouted “Feve Velazquez PRESENTE!” Feve, a beautiful and beloved leader of the trade union movement, gave her life at the young age of 27.

At 4 AM the next day, 40 hours after being detained, a vehicle from the US embassy picked us up and escorted us to the airport, (today the Monseñor Romero airport,) to deport me from my own country.

A week later the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) launched the October national offensive. In the middle of the offensive, on October 16th, the army of President Alfredo Cristiani, with the counsel of the United States, proceeded to murder Elba, Celina and the six Jesuits of my alma mater, the Central American University (UCA). We mobilized protests of every kind and at all levels, from vigils to civil disobedience in the U.S. Congress, the Senate, and at the White House, condemning the massacre and supporting the negotiations. The offensive and the slaughter at the UCA helped advance dialogue to end the war.

A truck bed with bodies of civilians 1980

Although the Salvadoran government released me, my name remained on the indelible list which is never erased. Thirteen years later when the United States donated new computers to the airport, the airport police detained me on a plane to the U.S. with the same accusation as before, “suspected terrorist.” They told me my name was on a list from the years of the war. They freed me only after the U.S. embassy called to say it was a mistake. Another time, when my U.S. passport was stolen in El Salvador and I requested a new one from the State Department, they refused to give it to me due to “irregularities” in my file. They finally gave me a new passport after my congresswoman, Nancy Pelosi, intervened.

A journalist asked me, “What has been the most difficult moment of your life?” Without a doubt it was the 40 hours I spent in the hands of the Death Squad of the Policia de Hacienda in the middle of the offensive in October,1989. It was the second time in my life that the Death Squad had orders to kill me and the second time that I escaped. It made me think of the 40 days Jesus fasted before he died. I remember the smell of urine and shit in the cell and the terrified screams of the tortured. In 40 hours I recalled every year of my life to that point. Naked, blindfolded, with my hands having fallen asleep after being tied behind my back and almost fainting, I thought of my mother, and I asked her, “What would you do in this condition?” She told me, “Hijo, aguanta el sufrimiento con dignidad, son, endure the suffering with dignity. “

“And what has been the most important moment of your life?” The most hopeful moment of my life was during the 40 hours I spent in the hands of the Death Squads of the Policia de Hacienda. When they were processing us in the Policia de Hacienda and the phone rang with a loud, long and powerful RIIINNNGGGGG, the police picked up the phone and hung up and in minutes it rang again, RIIINNNGGGGG, RIIINNNGGGG I knew that the campaign Eileen was organizing was generating thousands of calls demanding our freedom. It was a sharp sound and meant hope for life. When I couldn’t endure any more in the cell, I remembered the sound, recorded in my mind, and it gave me energy to continue resisting. It was a fight between life and death, like the struggle of Jacob who fought all night against the angel of death. I imagined the three Marias and the mothers shouting in the United States and in El Salvador VIVOS SE LOS LLEVARON! VIVOS LOS QUEREMOS! (YOU TOOK THEM ALIVE! WE WANT THEM BACK ALIVE!) : Maria, the chalateca hidden among the people, risking her life to accompany us, Maria Julia Hernandez from Tutela Legal fighting against the Death Squad of Alfredo Cristiani’s government, and Eileen Marie fighting against the government of Ronald Reagan. Thanks to them, once again I can say TODAY IS A GOOD DAY.

To continue reading previously posted stories for Jose Artiga, click the links below:

Story 1: The June 1st 2015 story

Story 2: The June 15th 2015 story

E n d o f s t o r y