NACERES JOSE ARTIGA ESCOBAR

(This is a continuation from the June 1st story. You can find it archived on our scrollbar if you have not yet read it.)

My mother dispatched my younger sister Hilda who found me early the next morning as I was coming out of my girlfriend’s house, reported what happened the night before, and instructed me to leave the country immediately. She had a message from my mother “If you love me, leave today.”

By 5 PM I was in Guatemala. Ivonne and her brother, Sergio, drove me across the border where I stayed with a family they knew. I worked in their chocobanano business for a short time. By 3 AM I was racing, carrying large sacks of bananas and having coffee with my new Guatemalan friends. I had little money, and a week later my family came with my clothes and some money.

Life as we knew it ended that June 27, 1980 at 10 PM. My family abandoned the farm. I left the country. There was no choice; it was life or death for all of us. As we tried to assess the situation over several months, I thought there was some mistake about my being a target of the government’s death squad. However, I discovered from a friend that it was very intentional. I was told these things do not happen randomly. There was a two- inch file on me with notes and photos. The only two theories we could figure out was it was either my participating with my girlfriend in delivering the packages to her cousin in the popular movement or our family’s relationship with our progressive priest. The one leading the death squad who came to our home in San Martin was Walter, a former classmate of mine. No one in those groups was told in advance who the targets were until they arrived at their destination.

I chose to see June 27, 1980, as the day I died. I also chose to see it as my day of liberation. At this point in my college career, I was two semesters shy of being an engineer. Now I no longer had to be stuck in that track. I could re-define myself and be whatever I wanted to be. Every day of my life became a bonus. I had a brand new life ahead of me. I say: “Today is a good day . . . “

Although my mother always supported me, my family did not share my same upbeat attitude. They were very worried and blamed me for losing our home and livelihood. They felt I had put them in danger. Slowly they began to compare our situation with others they knew and came to realize if the archbishop can be killed, anyone can. It took many years before my family lifted that blame and saw this was an actual war with thousands of innocent people dying. The media was blaming communists, and they knew I was not a communist. (Six years later in 1986, I returned to El Salvador with a delegation for the Romero anniversary and had a brief visit with my family accompanied by Lutheran Bishop Walter Grumm and Tom Ambrogi, a leader from the Archdiocese of San Francisco. My mother opened her arms to me, and my family and I reconciled. )

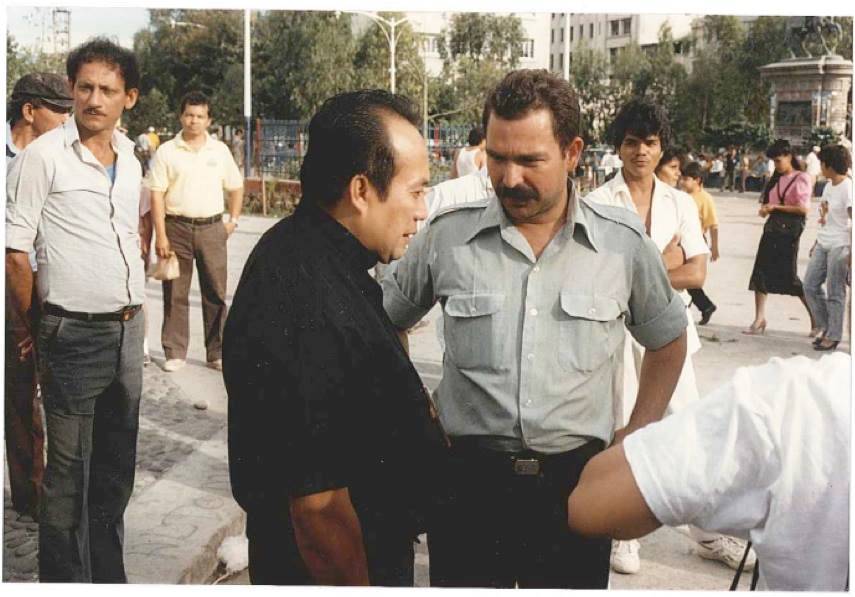

Lutheran Bishop Medardo Gomez talking with Jose in 1987.

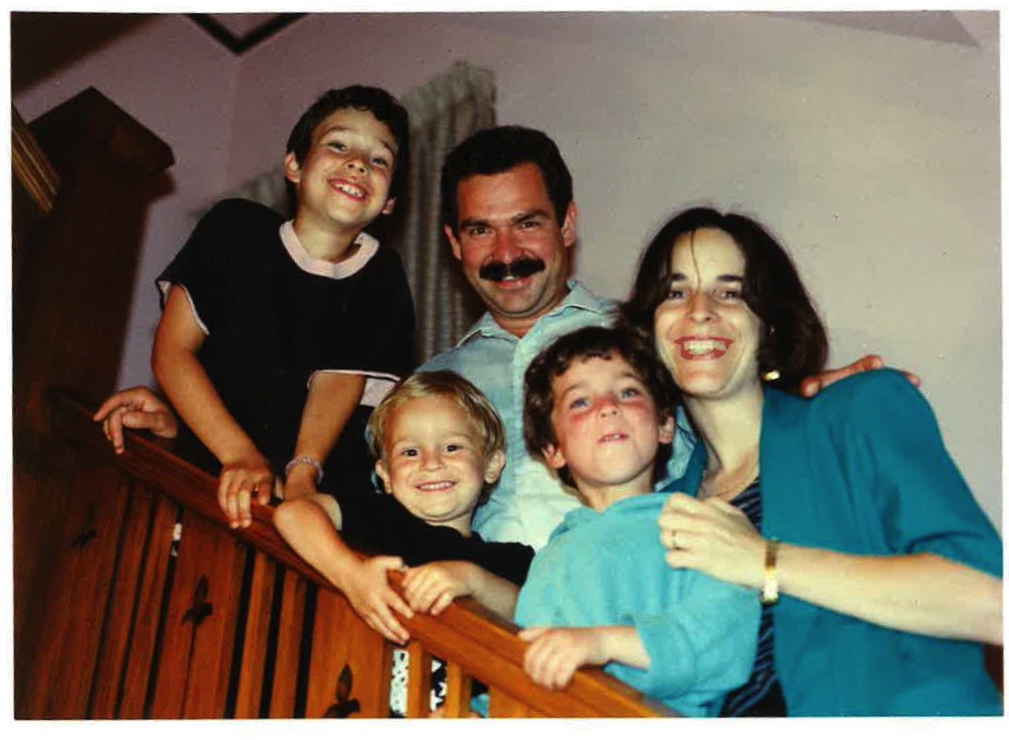

My mother had to sell the farm at a very reduced price. The neighborhood retains the family name of Colonia Las Artigas. My mom was able to donate the house and barn to a group of Spanish sisters who converted it into Colegio Eucaristico, an elementary school. They also added a high school to the grounds. Many years after the war, Eileen and I took our three boys to visit my boyhood home which the sisters gladly showed us. As I told the story of the day the military came, I placed my finger in the bullet hole in the door as if it were an open wound. That image and the giant mango tree in front of the house are two distinct images they will recall from that visit.

In the early 1980s persecution in Guatemala was even worse than in El Salvador and I quickly moved to Mexico. Their colleges were excellent, but funding was impossible to arrange. I worked a little while applying to colleges outside the country. The University of Texas in Austin accepted me and I miraculously obtained a study visa from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City. Meanwhile my college girlfriend was targeted by the death squads and left for Europe. She suggested we break off all contact for our mutual safety. (I saw her again in El Salvador in March of 2005 at the 25th Romero anniversary.)

As a Spanish speaker starting college in Texas what I didn’t understand was that I could have taken an English course and then probably finished my final semesters in engineering and graduated on schedule. Instead I started my classes all over again. However, El Salvador’s situation worsened dramatically, and I felt compelled to address it. Therefore, I put my academic career on hold until years later when I earned my BA from Catholic University in Washington, D.C. at age 33 and my Masters degree in economics from San Francisco State University when I was 40.

Murders and massacres were running rampant in El Salvador. The churchwomen being abducted, raped, and killed drew much international attention in December 2, 1980. The Jesuit priests being killed on the UCA campus near the end of the war in November,1989, and all the massacres such as Rio Sumpul on MAY 14, 1980, El Mozote (December 11, 1981) in between were radicalizing families and communities. As the pressure became great, people needed to collectively make choices in order to survive. A turning point in El Salvador was using planes, which the guerrillas didn’t have until the guerrillas got anti-plane missiles. You just move from one level to the next. The people needed to organize to defend themselves. Many NGOs formed as a result of that pressure.

Living on our middle class farm in El Salvador there were always members of the poor families who lived in our house from time to time who gave me some limited awareness of the poor, but my true transformation regarding the poor occurred in Austin where I lived and worked in Casa Latina. I volunteered from 11:30-1 PM each day laying out the copies of articles and literature on the situation in El Salvador at a table on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin. Rich students from El Salvador would come to my table and challenge me claiming there were no violations of human rights by the Salvadoran Armed Forces or government. As I read the articles on El Salvador I started to remember the bodies I had seen on the mayor’s porch. I was able to see the bodies through the eyes of people in the U.S. Through re-telling the stories to others that I had witnessed things became clearer to me than they were when I was living through it. It’s like the guy hurrying to the church to pray but misses the beggar on the sidewalk. Sometimes you need a shock to move forward. It’s like a person who loses a leg and they think they’ve lost their life, but someone reminds him, “No, no, you just lost a tiny little leg. You still have your other leg; you still have your brain, your eyes; your ears.”

I studied English and practiced with the students. I worked a full-time job on campus washing dishes and I had meetings until 4 AM discussing how to change the world with my friends from Cuba, Uruguay, Mexico, Paraguay, Chile, Venezuela, and the U.S.

The summer of 1981 I joined a group of students at the University of Texas and we raised money to visit Cuba with the Antonio Maceo Brigade. It was a totally refreshing and different world than any of us had experienced. Cuba was a socialist model I had never dreamed possible. We visited many communities and discovered that a small country can re-distribute their goods to all members of society. I learned that universal education and universal health are possible. I was coming from an experience in El Salvador where only 1 % had access to college. Here in Cuba everybody could go to school from kindergarten all the way through college. Everybody had access to healthcare and people did not die of diarrhea or other curable diseases. That experience was engraved in my mind, and I wanted to struggle for everybody in my country to have access to health and education.

I became active in re-learning about El Salvador from the nascent solidarity movement that was emerging in both the secular and religious sectors within the States. I drove from Austin to Los Angeles to a conference on October 4-5, 1980, where we formed CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador. Salvadorans at the conference invited me to move to San Francisco and work in solidarity full-time. I said, “Yes!”

In a short period of time I had made many friends in Austin. My departure was a great potluck party at Casa Latina with pots of food, live music, and gifts to take to California.

On March 20,1981, I did exactly that, leaving Austin to help organize the solidarity movement in San Francisco. It would be difficult to devote myself to fulltime organizing work without getting a job to support myself. I approached a progressive priest, Father Cuchulain Moriarty, with a proposal at the recommendation of Carlos and other Salvadorans who had begun working with the Church. I asked him if he would provide me with room and board in exchange for my services as a sacristan on Saturdays and Sundays at his parish, Most Holy Redeemer. He sent a friend and colleague of his, Eileen Purcell, a young fulltime organizer at Catholic Social Services of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, who had co-founded the Archdiocesan Latin America Task Force and the Committee to Stop the Deportations, to check me out. We met at the storefront office of Casa El Salvador Farabundo Marti on 35572 20th Street in the heart of the working class Latino community and hit it off. She gave the priest a positive report on me and I was able to move into my new home at Most Holy Redeemer in the Castro District where I was quickly “adopted” by Irene, the longtime cook, and Patsy, the parish secretary! I received unlimited food and my choice of any clothing that was donated to the church. I also had access to donated church vehicles in exchange for weekend work for the priest. {In 1983 Jose and Eileen marry.)

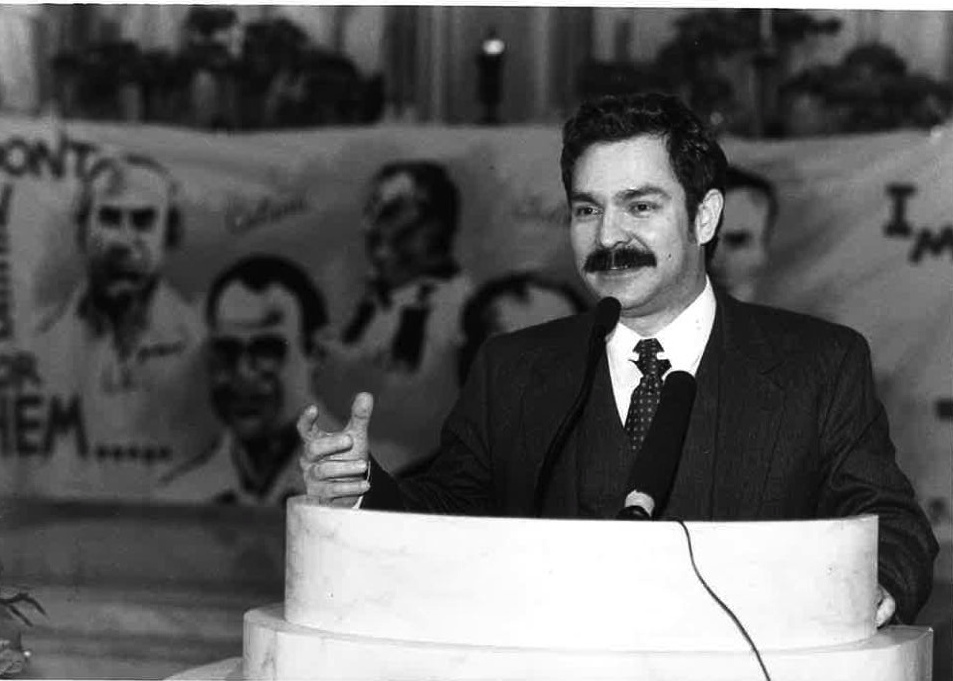

Eileen in 1989 raises her voice for the martyred at UCA

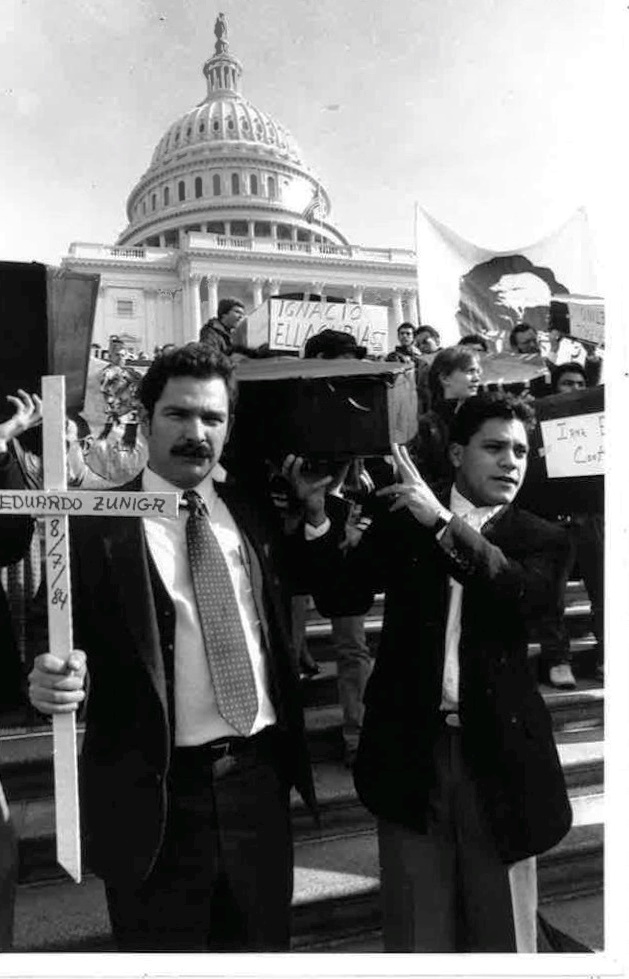

As executive director of the Casa El Salvador Farabundo Marti from 1981-1985, we advocated for the rights of Salvadoran refugees. We helped launch the sanctuary movement that helped refugees, denounced human rights violations, and called for a halt to U.S. intervention. The sanctuary movement was very vibrant and became a national effort. Lutheran pastor, Gus Schultz, and Eileen organized the first cluster of Sanctuary congregations who declared public sanctuary on March 24,1982, announcing their public, corporate stance to “defend, protect and advocate” for the rights of Salvadoran refugees in the United States and calling upon the U.S. government to stop the deportations and stop the military intervention causing the exodus of people from their land. Five congregations in the San Francisco Bay area and one congregation in Tucson, Arizona, held simultaneous press conferences to announce their decision. Four refugees told their stories. I was one of the first refugees in sanctuary that day. Neither the communities or the refugees knew how the government would react or whether we would be arrested, and in the case of us refugees, deported. It was national news. Though there were thousands of refugees like myself with powerful stories to tell, many were afraid to share them publicly for fear of retribution. A few of us overcame our fear offering our personal testimonies with the hope that we could change hearts and minds to impact U.S. policies. We shared our stories and overcame our fear because we knew the churches were committed to protecting us. (The risks of deportation and then resultant death after being returned to our own countries was very real.) The churches declared sanctuary even though their lawyers advised against it cautioning they may lose their 501©3 status. The harder the government cracked down on the sanctuary movement, the more the movement grew.

Within a few years, hundreds of refugees told our stories to congregations, in house meetings, at parish forums, and more than 500 congregations declared public sanctuary across the country. Many cities like San Francisco declared a city of sanctuary that three decades later still protects the undocumented from immigration police.

Jose in 1989

The 1980s was rich in solidarity for El Salvador. We benefitted from a history of solidarity and organizing in support of Mexican farm workers, political refugees from Argentina and Chile. With the revolution in Nicaragua, the soil was fertile for us Salvadorans. We organized a national network of organizations with hundreds of local chapters, which enlisted thousands of people working day and night to denounce the violation of human rights and U.S. military intervention. We held thousands of activities including hunger fasts, walks, concerts, marches, vigils, posadas, congressional visits, civil disobedience, fiestas, and thousands of educational events and house meetings. Lots of fundraising was required. A whole crop of volunteers came from the Santa Cruz area colleges to volunteer their time as a result of the outcry they were hearing. Imagine planting anything in your garden you wish and it flourishes ten times what you expect. We were mobilizing people, gaining small victories, and seeing change thanks to so many!

In 1989, when the Jesuit priests were killed, we engaged in civil disobedience to draw attention to the horror of it. The assassination of the Jesuits helped to force the end of the war. We were asking for the impossible; to stop U.S. intervention in El Salvador and to end the war.

This solidarity was extremely effective. During the eighties, U.S. government immigration policy permitted nearly 100% of the refugees from Cuba into the country but denied 99% of asylum refugee cases from El Salvador and Guatemala. Why? Because the refugees’ stories contradicted the U.S. foreign policy and the party line that insisted there were no human rights violations by the Salvadoran government and its U.S. trained military. Salvadoran refugees told a very different story than the Reagan administration. People who visited El Salvador came home with stories that sharply contradicted the U.S. government’s position.

The sanctuary movement effectively challenged the U.S. policy. In the historic legal case, The American Baptist Church et al vs. Meese (and later Thornbourg) the movement sued the U.S. government for violating the legal rights of Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees and breaking its own laws as well as international law. After ten years of legal battles, the government agreed to settle the case. Political asylum applications for more than half a million Salvadorans and Guatemalans were reopened. With political asylum we kept organizing and demanding residency with a path to citizenship and in 1996 we got it.

SHARE began in 1981; Eileen and Gus Schultz joined the Board of Directors in 1983 and Eileen became the Executive Director of the SHARE Foundation in 1986. SHARE’s offices were located at the Theological Seminary at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D. C.

In 1986 when Eileen became the Executive Director, she and I moved to Washington D.C. with our one and a half-year old son, Camilo. While Eileen led SHARE, I continued my work on human rights through the Interfaith Office on Accompaniment, an extension of the human rights work we did in San Francisco, including a successful campaign to free Ricardo Calderon, the former president of the National University.

A year later, in 1987, our second son, Rutilio was born followed by Alejandro in 1989. While we lived in Silver Spring, Maryland. Eileen and I were blessed by the support of Eileen’s family who provided tremendous support. Raising three boys while both of us were committed to the struggle for human rights and social justice required the help of our extended family and the beloved community and we deeply appreciated everything they offered us.

To continue reading, click here.