CHRIS HARRISON

Part 1

Esta historia se escribe en Español = This story is also written in Spanish here.

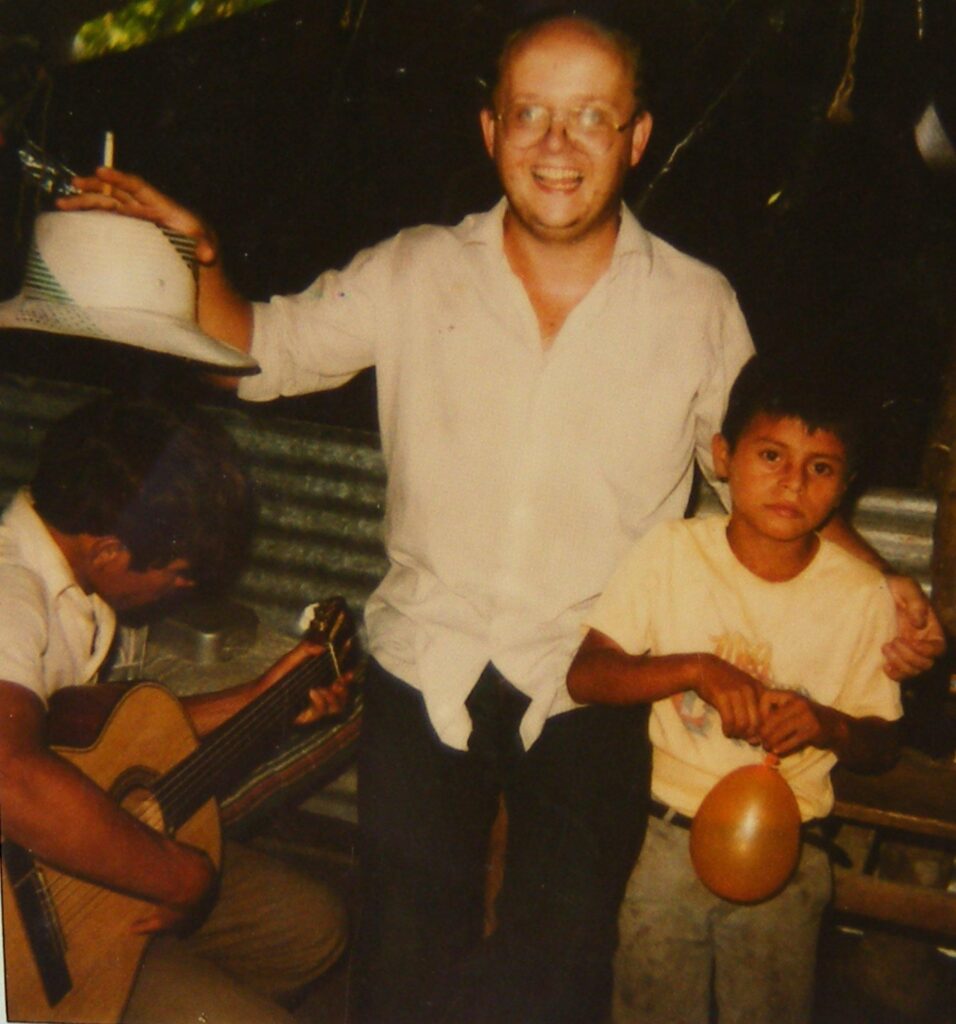

“I went to El Salvador as a seeker with no fixed ideas, just wanting to learn. The experience was fantastic.”

Editor’s Note: We are immensely grateful to Chris for candidly sharing his vivid memories of serving in El Salvador for two years during their civil war. His memory for names, dates, places is remarkable. Over several months, several interviews, and ongoing communication, masses of information and volumes of files of photos are available. This is a condensed three-part story which still barely scratches the surface of Chris’s experiences.

Growing up immersed in a small, remote village in England, divergent thinking and attitudes were unheard of in Chris’s world. Even as a child, that unaccepting, provincial perspective never set well with him, and he always challenged it. At university his world exploded with thinkers and alternate viewpoints. Here he thrived and came into himself.

When an opportunity came to visit and experience El Salvador during their civil war, the event catapulted him into action forever changing him. Life in a war-torn developing country outside the pages of textbook gripped his soul. He returned to university and changed his dissertation to tell about it. Then haunted by what he had seen two years earlier, Chris left a lucrative job in the IT field and returned a second time to work as a volunteer in a Jesuit-run refugee camp for folks forced out of their homes by the military. He performed myriad roles from mid-wife to picking up wounded locals in ditches to treat in the hospital. His later role involved accompanying folks as they returned to re-build their communities. Chris had the good fortune to interact with some of the bravest, most faithful people – humble locals, devoted internationals, and influential Salvadorans, including Jesuit priests who later were assassinated at UCA, whose martyrdom is forever celebrated annually with a candlelight vigil at the university.

Chris’s life was forever transformed as a result of El Salvador – first intellectually, second pragmatically, third spiritually.

Here begins his compelling story:

Raised as an only child born in 1959 in a conservative, parochial English village, I entertained myself by challenging my parents when they made disparaging comments about others who differed from them. I attended school about twelve miles from our village where I was a decent cricket player. Just to needle my folks, I had received their permission to invite a member of a visiting cricket team to spend a weekend at our home. Little did they know I was bringing a six-foot three-inch member of a West Indies team. Seeing their mouths drop to the floor when he appeared at the door was worth the reaction. They managed to behave impeccably while probably gritting their teeth. I grew up watching home movies of my parents in colonial service in Rhodesia in the 50s where my dad served as a teacher and builder.

The Anglican church to me was a church of “bells and smells.” I attended a primary school operated by the Anglican Church. My family participated in church social events. My mother served on the village parish council. When I was fifteen, my mom died from a stroke after being unjustly accused of stealing church funds. I have always resisted any institution of hierarchy.

While I was attending university in Cambridge from 1977-81, I became exposed to many different points of view. David Cornwell, the writer John le Carre read us ghost stories and engaged us in political discussions late into the night. Noam Chomsky, ministers, political leaders, and philosophers provided forums for debate and discussion. Chilean human rights activist Isabel Morel Letelier was another person I hold in high esteem. Even after she and her husband, Foreign Minister Orlando Letelier, were exiled from Chile and he was killed in a car bomb in Washington, D.C., she continued to raise the country’s consciousness which earned her various human rights awards. Another woman who worked on behalf of human rights abuses in Chile was Sheila Cassidy. An English doctor who herself was a torture survivor, she wrote several books including a favorite I re-read often, Audacity to Believe. Two South African human rights activists come to mind as well. Desmond Tutu, is well known. Not as well-known is Joe Slovo. Cambridge was a magnet for these divergent viewpoints. They were refreshing to someone like me raised in a narrow-minded, mundane environment.

For my B.A. dissertation I was working on a biography of a French political theoretician, Regis Debray, who worked with the Castros and Che Guevara in the 1960s. At the same time, I was studying modern Latin American history. I found myself gravitating to the contemporary political situations in Central and South America with the dictators and regimes taking control and the guerrilla movements springing up in opposition. Having studied Spanish, I could read the news in its original news sources. The Cuban Revolution had happened, as well had the coup d’etat in Argentina, insurgency in Bolivia, etc.

I worked in the Netherlands from 1984-86. A friend was heading to El Salvador in 1985 inviting me to join her during my summer vacation. A chance to witness a Latin American country amidst its civil war and hear their stories while riding shotgun intrigued me. Our white faces served as a bulletproof assurance of safety to the people by serving to persuade the military to show restraint from harming them. I arranged to change my dissertation topic at the university to this more current topic and went along with the group to El Salvador. Initially my interest was just academic, one of intellectual curiosity.

{Note: As a reminder for those unfamiliar- El Salvador’s civil war lasted from 1980-1992.}

I could not “unsee” what was happening in El Salvador, and with their civil war continuing, in 1987 I applied to the JRS, Jesuit Refugee Service, that was building Calle Real, a large refugee camp northeast of San Salvador near Apopa. It was built to relieve the congestion of the Archdiocese’s refuges at the San Jose de la Montana seminary, the Basilica del Sagrado Corazon, and in Santa Tecla, among others.

At this point I transformed from having only an intellectual interest to developing a pragmatic interest in which I could engage to be of help. I left England with no work contract; it was all very open-ended. I wasn’t even a Catholic. I wasn’t sure what I would specifically be doing but had seen a humble people whom the world largely was unaware of suffering great atrocities.

To this point many people had been uprooted from their small towns and villages, many of which had been burned to the ground by the military. These families were living in conditions such as in city church buildings that provided them sanctuary from the military. However, they were very crowded, there was no room for exercise; the people were becoming restless for land to plant crops, to be the people they were accustomed to being rather the prisoners they were living as. Calle Real was the site the Catholic Church acquired to bring larger groups out into the countrysides still giving them sanctuary while allowing them to spread out.

Two nuns were in charge of the camp under the direction of the archdiocese, and four other professionals – a builder, an agronomist, a tailor, and a boudeguero, manager of a storehouse where supplies and tools were given out, were hired by the Archdiocese to train and equip the desplazados to resettle their homes. Eight internationals lived and worked in the camp coming and going and rarely all there at the same time. The camp had a clinic and hospitalito. We were to serve in an accompaniment role. Whatever needs the people had, we were to find a way to assist them. We taught literacy classes, worked in the kitchen, transported them to medical appointments and offered moral support and shoulders to cry on.

A big red pick-up truck with a cage on the back for people to safely ride, the most conspicuous vehicle on the roads, was a gift from Cardinal John O’Connor and the NY Archdiocese. (Cardinal O’Connor was known for his vocal opposition to U.S. support of military regimes in this area as well support for the Nicaraguan Contras). We used the truck to get people around to doctors’ and hospital appointments, bring in supplies, etc. I often drove the truck. If someone had a hospital appointment, we drove the person there at 6:00 AM to wait until his or her appointment which may not have been until late that afternoon. If we sensed their security was at risk, one of us waited with the people so they were not kidnapped. We drove them back to camp at the end of the day.

Our friend, Frankie, had his experience with the death squads one Sunday morning while driving people to visit their family members in Mariona Prison. Holding an American passport was priceless which he, a California native driving our truck discovered after the military pulled us over in a roadblock; they beat him up, and pistol whipped the women passengers. The military assumed he was Salvadoran due to his dark skin. After he showed his U.S. passport, we were left alone with an “Oh, shit, gringos” comment.

The U.S. government had made it clear to the military of El Salvador that if any other American was killed, they would cut off all funding immediately after the U.S. Maryknoll nuns and various journalists were killed creating an international crisis and bad optics for their military. It was impossible for them to continue their efforts without U.S. backing. The military showed more subtle signs of displeasure; for example, we once discovered a young, local supermarket worker named Andrea Urbina’s mutilated corpse on the nearby bridge in the shape of a crucifix. He had done nothing but go to the nearby stream to wash up before going into work. The army had been laying in wait to ambush him since 2 AM. They wanted to simply to make a point by instilling fear into those living in the refugee camp.

Within Calle Real each day was different; however, certain things were required to happen. Our roles and responsibilities were fluid as we all pulled together to meet the needs of the people. The archdiocese assigned the nuns and priests to oversee the work. Visiting priests from San Salvador came to bring visitors, perform mass, and teach catechism. Jon Sobrino and Jon de Cortina regularly visited the camp. Another refugee camp, Fe y Esperanza was a Lutheran-run refugee camp that Bishop Gomez oversaw. He and the Catholic priests worked together to provide a safe haven for those at risk of harm by the military.

Yes, we were all at risk of danger but didn’t think about it on a daily basis. In fact, we pushed the envelope thinking we were immune to the military because being white and being associated with a church group basically protected us. Priests were getting death threats by paramilitary groups every couple of months. The Catholic church radio station YSAX and the UCA office with the printing press got bombed on a regular basis. We got hassled by people in ostensibly civilian vehicles with unregistered plates. Late one night while the camp was cordoned off by the army, one of the officers shot very near me as a scare. He came around the following day to taunt me. It was just a part of routine life during war.

On Saturday, January 16, 1988 a couple of platoons from the First Brigade army invaded the camp bringing in a defector from the FMLN to identify people he knew. Ordinary refugees banded together to physically prevent the targeted individuals from being taken away for “interrogation.” Out of retaliation the following day the military surrounded the camp and shot at the hospital where they knew wounded locals were being cared for which was unauthorized; however, if we had not done so as a humanitarian gesture, they would likely have been tortured and killed. One person was seriously wounded that night. It was unexpected and pretty scary to be fired at by thousands of rounds as well as half a dozen 40mm grenades and an anti-tank rocket. They knew we were caring for locals because an infiltrator had reported it. (Infiltration was a prevalent problem as the military paid locals for information they received.) The military desperately wanted to interrogate them and burst in one day. On Sundays locals were permitted to visit their friends and family members at the camp. (The same was true of the prisons. I know because I sometimes drove people to a prison to visit relatives). No security clearance for locals was required to make visits. This made it easy for military to sneak in infiltrators. Right after that incident my dad asked to come visit me. I told him the timing was not good. He had fought the Fascists in Italy and understood.

The hospitalito and clinic were run by an American nun who was a qualified doctor along with two other part-time doctors, one American and one Salvadoran, two nurses, and a nun. Although I has some rudimentary first aid training in the Netherlands, I was not prepared to deliver babies or assist in surgeries. If the professionals were busy doing other things, some of the rest of us who had some healthcare experience had to do the best we could. I am not a squeamish person, so I didn’t mind doing what intervention I could to help where needed. It was sometimes difficult to cope especially if the FMLN has declared a transport ban making it hard to get help from outside or take emergency cases to the hospital in the city. At times we took the risk to drive emergency cases during the ban hoping that our truck would be recognized for what it was.

Dr. Dave Evans, a West Virginia native who survived the Vietnam war after losing both legs devoted his life to traveling the world to help fit amputees with prosthetic limbs in war-torn countries. I had the privilege of watching him work miracles in our hospital. After the war some of us organized in an effort to nominate him for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Different volunteers within our group of internationals had different reactions to what we were witnessing. Two of them went to the mountains and actively supported the rebels. The American nurse performed healthcare within a controlled zone. She was demobilized along with combatants following the 1992-3 Peace Accords. I had no personal problem with armed insurrection. I had the British equivalent of ROTC training in school being trained in armaments but held no romantic notion of fighting for the underdog. In fact, I was invited to join the rebels several times. However, I declined for several reasons including that I felt I could best serve in the capacity I was serving.

The archdiocese negotiated an agreement between the FMLN and military to exchange wounded combatants and prisoners of war from each side to the International Committee of the Red Cross. The commanders of each side knew one another well and respected that international organization’s work. When the local hospitals were unable to treat the wounded, the FMLN was allowed to ask the Red Cross to transport those with the most serious wounds, such as serious head/brain injuries, back injuries and amputations some of which were the result of stepping on a toe popper anti-personnel mine, to fly to Cuba for treatment. The hospital at Calle Real housed them until transportation could be arranged. When they recovered, they could return to El Salvador.

Calle Real began winding down in mid-1988, about three years after it began. At that point the people were war-weary and ready to take their chances and leave, even though the war continued and Peace Accords did not come until 1992. Accompanying folks back to their villages was my second major role while serving in El Salvador. Various church groups and later the UN were asked to do this to protect the people as they returned from camps hoping to resettle their communities. I worked in the Suchitoto, Santa Marta, Guarjila/San Antonio Los Ranchos, and Guazapa areas. Access to Suchitoto and Guazapa were heavily controlled by military. The nuns had easier access through the frequent roadblocks than the rest of us. Our work involved building small huts with meager donations from international sources for tin roofs, lumber, black plastic, and tools. In the one community that I helped build, we built a dozen small shacks, planted corn and beans, and set up a water supply. These settlements were located in various departments around the country, including Cabanas, and Chalatanango – specifically in El Higueral in the parish of San Francisco Morazan.

Over time my intellectual transformation turned pragmatic transformation turned into spiritual transformation. I went to El Salvador as a seeker with no fixed ideas, just wanting to learn. The experience was fantastic. It was the faith of the Salvadoran people that is so genuine, loving, welcoming, honest, inviting in its simplicity that moved me along my own spiritual journey. Everything I experienced with the campesino community — their natural goodness was in contrast to regimented religion. Community and caring for each other are central to their lives. Anyone who can maintain their sense of community and morality and love for one another while getting their asses shot off is okay by me. That is faith in action.

I saw that day in and day out. I watched nuns and priests serving in ways that their formal hierarchy would never approve of if they had known, but it worked in that setting with the Salvadoran people. As I said earlier, I’ve never been a fan of hierarchy. I witnessed the people constantly pushing the limits in how they cared for one another under dire straits. I would love to be able to share some of the stirring stories that happened every single day, but people are still being killed in that country today for some of those renegade, unauthorized, behind-the-scenes actions. So they shall remain undisclosed in order to keep people safe. I find that frustrating and very unfair to these heroes and heroines. I feel I brought that back from El Salvador and try to use it as a role model in how I live my current life.

I may have extended my stay had it not been for a stent in a San Salvador jail which consequently marked my card. [see next month’s story which begins with this incident.]

Next month begins with the experience that sent Chris back to England and how he carries his Salvadoran life with him now.