STORY OF MARIA MORENA PALMA PALMA

“If I had been in that first group, I would not be here today sharing my story.”

Esta historia se escribe en Español = This story is also written in Spanish here.

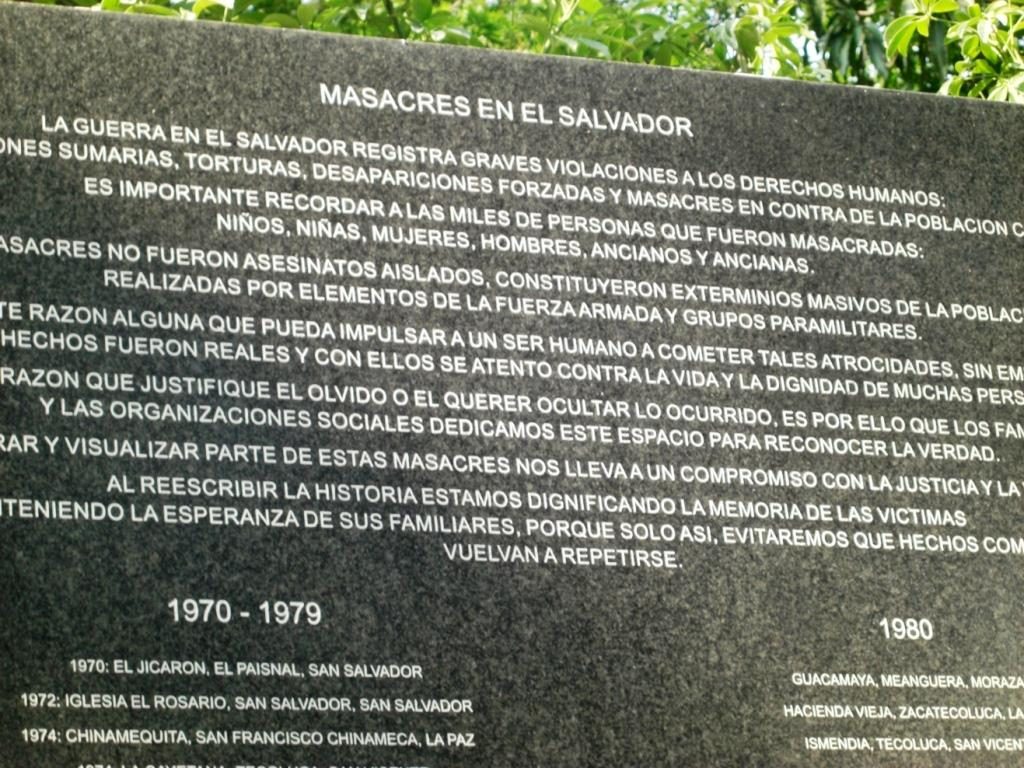

Editor’s Note: Over the past several years I have become strangely fascinated by the “survivor’s guilt” syndrome. We asked our CRISPAZ coordinator if he could arrange for us to interview someone who had survived a massacre. He arranged two such interviews. Maria was a teenager when she survived one of the massacres in the Sumpul River area of the Chalatenango department in May of 1980 during the country’s civil war. In Maria’s case, she not only survived but also is responsible for saving her younger sister.

For those interested in reading a full narrative account of this abomination, I would recommend Yvonne Dilling’s compelling book In Search of Refuge.

Were you aware as a teenager growing up in that volatile area of your country what was leading up to the series of massacres along the Sumpul River in 1980?

My understanding is that the UTC, Unidad de Trabajadoreo del Campo, labor union began in our country as a result of workers who were being exploited. In my area they consisted of many coffee finca workers. Examples of their living conditions included not having decent places to sleep, being treated harshly by the land owners, and receiving very poor salaries. There was no opportunity for campesinos to own land. They got fed up and began to organize themselves to improve those conditions. Organized unions fell into the same category as university faculty and clergy: they were threats to the existing government resulting in force against them by police and military. The soldiers came and killed anyone they even suspected to be involved in these organizations. It wasn’t just the participants themselves who were the victims, but there were numerous massacres of children and innocent people in our area as early as 1979.

How did your family react to these oppressively alarming acts?

We were all frightened, of course. It was not even merely the local police but the National Police who were selecting children to be killed. I was 16: my birthday is September 6, 1964. My parents, like many families in our area, went to the forest at night for our safety.

Río Sumpul near Las Pilas, Chalatenango

When did this all reach a crisis level?

We got news on May 13th that soldiers were approaching. The villagers of Los Minos saw the large number of them and quickly moved to another village, Los Calles. We thought there were not too many soldiers coming, so the people ran from the offensive and away from Las Vueltas. The military exploded bombs and grenades into the woods. We ran into a small river near the Sumpul River.

There were many killed in a massacre there already, including older people who had been unable to run fast enough. I was with my mom and two older siblings and my 18-month-old sister when the offensive came. My father was not home at the time.

We didn’t know what to do because we saw the helicopters above us and the soldiers below us and could hear the bullets flying. We simply ran to save our lives.

How long did this continue?

It was late in the day. The soldiers did not continue to follow us but instead concentrated on the other group. My family moved on to Los Naranjos. People told us to go to Las Aradas because the massacre there was over. By this time it was 8 P.M., and a group of guerrillas escorted a group of the people away.

My sisters, mom, and I stayed in the other group. The guerrillas told us they would take our group in the middle of the night. At 4 A.M. they escorted us out during heavy rain. It rained so hard we couldn’t see our own hands. During that time a child was born. It died due to lack of protection from the elements.

I was carrying my little sister on my back this whole time. At 7 A.M. we continued, and it was so cold – every time I tell this I want to cry. It was just too cold for my little sister. All the children were crying from these extreme cold, wet conditions, fatigue, and hunger. When the sun finally came up, it helped a little.

Did your tiny sister survive this ordeal?

We were walking in different lines when I spotted a man in front of me carrying plastic. I told my mom I was going to ask him for a piece of it. I wrapped my tiny sister in the plastic to insulate her body and try to warm her. Finally, she began to breathe normally again and warmth started to return to her body. I have no doubt that I saved my sister’s life.

Was this long arduous trek the end of your ordeal?

No, at that point we heard soldiers shouting and shooting, helicopters bombing, and people crying. People told us not to go down to the river. Soldiers were herding people in one area to begin the massacres. The soldiers who had been following us stayed in one area.

Later in the day persecutions continued. The Salvadoran military had coordinated their killing with the Honduran soldiers on the opposite side of the river to kill anyone who crossed the river.

They took us over another route that was more difficult to traverse to a place called La Montanona – (Big Mountain.) A family from the village came to meet us at night and thank God, offered us a place to stay for the next day until we returned to the villages after the military had left.

How did you survive during your time in the mountains?

We survived on roots and an occasional banana. In the middle of it is a pulp we could burn to eat. It was a very hard time. There was nowhere to rest, and it was the rainy season. My little sister lost her ability to walk because she was so weak.

How do you reconcile surviving?

God protected us. The helicopters could not see us hiding in the woods. We could hear the screams of the people and stayed away from that area. If I had been in that first group, I would not be here today sharing my story.

Were there survivors from the river?

Some people survived by crossing and lying to the Honduran soldiers by claiming they were Honduran citizens in order to save their lives.

What was the most disturbing act of human rights violations to you?

Although I didn’t personally witness this, I do know individuals who did. That was of the soldiers who took the children, threw them up into the air killing them with their bayonets as if it were a game. This was common.

What did you find out after this event ended?

If my family had been among the first group to try to pass, we would have all been massacred. Every one of that group was killed. There were 250-300 massacred in that group.

After the Las Aradas massacre, many people began reporting these events and our situation to the UN. This created an international awareness. UN representatives arrived and began to help search for and identify bodies, many of which had washed down the river.

They also set up two UN refugee camps such as Mesa Grande across the border in Honduras for those Salvadorans who had been able to escape. Not all went well in that setting, and eventually they needed to move the camps deeper into the country rather than at the border. Groups moved into the camps at different times. Priority was given to areas where the military invasions were stronger.

Did your family live in Mesa Grande? Can you share a bit about it?

When we could no longer endure on our own in the mountains, we had no choice but to go there. Mesa Grande was born out of a necessity of the people. We remained there for a year and a half, from 1983- October, 1984.

At first it was nice because we had clothes and food. There were teachers from an international presence, priests, doctors, organizers who planted crops.

There was pressure to join the guerrillas. Later I joined the guerrillas as a cook and nurse. Then the whole family returned to El Salvador.

Can you share your experience of returning to your country?

When we wanted to return to El Salvador, we could not because the military had burned down all our houses. We were unable to work because, when we left so suddenly, there was no time to plant the maize crop, and so there was nothing to harvest to sustain our families. We had only our families, and we reminded ourselves that when we left during the rainy winter season, there had been no time to pack a suitcase. We left wearing the clothes on our backs ready to roll in the dirt to hide when the soldiers chased us.

Editor’s Note: Maria ends by thanking us for supporting her and her community for today’s opportunity to tell her story. “It means a lot to share our history” she insists. I still sit stunned writing this four months after hearing it. Its impact has not softened. I vividly picture Maria’s tears while recounting these experiences after 33 years which are still very raw. Yes, she and her family survived. But so many others did not. And that may forever haunt her.

However, like a local Auschwitz survivor recently told a radio audience, “When I share my burdens with others, they become lighter.”