“I see myself as a Pipil indigenous person and try to carry on those traditions through weaving.”

Esta historia se escribe en Español = This story is also written in Spanish here

Editor’s Note: To rewind the tape over 80 years, let’s recall a gruesome part of El Salvador’s history referred to as matanza (killing.) In a nutshell, the Spanish landowners who were busy expanding their estates and cash crops from indigo to coffee and cacao had been exploiting and abusing the peasants working for them for decades. At first the peasants were still permitted to grow crops to sustain their families. As the Spaniards’ greediness for land and profit increased, their treatment of the peasants deteriorated to what amounted to indentured labor and NOT allowing the peasants to grow subsistence crops on their land. Soon the mistreated indigenous people were pushed off the land altogether causing civil unrest. The conditions were ripe for the Pipil Indians in the western part of the country to lead a revolt-the peasant uprising of January 22, 1932, called La Matanza. Sadly, this resulted in tragic consequences for the Pipils, who didn’t stand a chance against a much better armed military that used the incident as an excuse for ethnocide of basically the entire indigenous population and its culture. While the rebels killed around 100, the military struck much harder killing between 10,000 to 40,000 peasants. Anyone with Indian features or who wore Indian-styled clothing became a target. The few indigenous people who managed to hide and survive abandoned their traditions and clothing quickly. In short, they lost their identity to fear. (If you want more details, see Matanza by Thomas P. Anderson. He makes strong connections to the country’s more recent civil war.)

Knowing two small areas in the country remain where descendants of the Pipil Indians still live, we wanted to interview someone with Pipil ancestory before no members survive. This group of indigenous people is believed to be descended from the Mayan and Nahuatl people of pre-Colombian times. Our coordinator arranged for this to happen in Panchimalco, located high up on a hill outside San Salvador. Descendants of the Pipil Indians fled here from the Spanish during the 16th century. Some records indicate the town was settled as early as the 11th century.

I was born here in the Panchimalco Indian Village on November 1, 1945, and raised in this same area. This structure is now part of the Casa de Cultura or House of Culture, which is preserving the Pipil culture by displaying handcrafts and other traditions of the Pipil Indians. (The area we walked through coming into this lovely courtyard is a museum filled with art, items the Pipils would have used on a daily basis, pieces of excavated pottery, etc.)

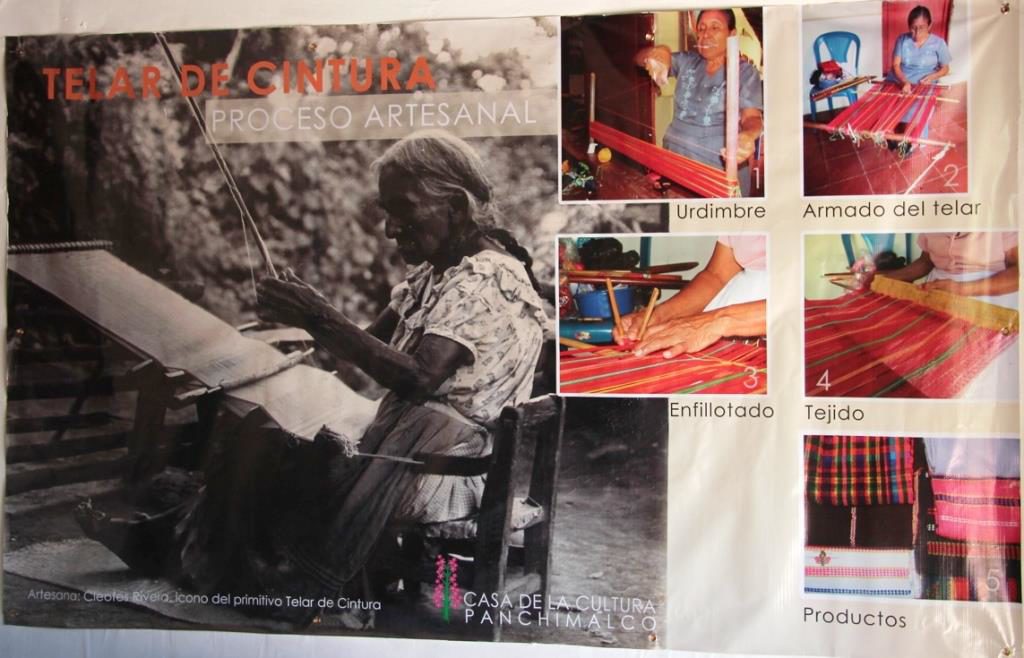

Although neither my parents nor us kids ever learned to speak the indigenous language of Nahuatl, I remember my grandmother speaking a little of it. That is her up on the poster over there, weaving just as I am doing here now. When I was two years old, my mother left me because she got re-married. I have four siblings – two brothers and two sisters.

This was a very humble town when I was growing up here. There were only a few houses. Now it is very settled. Most people made a living from agriculture and coffee.

My grandparents raised me. They were very poor, and I needed to work when I was six years old. At age eight I learned to carry the water and bake the bread to help out. When I was eleven, I learned how to weave and make the textiles that our people have always made. When coffee was ripe, I went to help harvest the beans.

On this very spot we are sitting is the place I used to go to school as a child. At that time it was a small wooden house with wooden columns rather than concrete ones. My grandma required me to attend school. I remember her telling me that if she did not send me, the authorities would come and put her in jail. I liked school and went to classes through third grade when I was seven. I passed into the fourth grade and begged my grandma to allow me to continue school, but she had no resources for me to go any further.

I joined a club called Daughters of Mary, which I liked, but because of the many duties of my weaving job, I had to quit the group. I did continue to attend Catholic Mass, though. (Note: The original Pipil Indians had developed a highly organized social system. Their religion was based on the cosmic interaction of natural forces. Most present-day Pipil Indians in Central America align themselves with the Roman Catholic faith.)

My biological mother died when she was very young. I buried her. I was her first daughter and my sister, Katalina, was her second. Our two brothers died during the war in 1981. They were drunks. Someone found one of my brothers dead along the road. The other one died at home.

Many people had family members who disappeared during the war. There was a lot of fighting in this area. At the summit of Cerro Chulo Mountain near here is a place we call Puerto del Diablo (Devil’s Door.) At that time during the 1980s, the nickname was “Door of Evil.” This is a place that the military used to bring and dump bodies. I suppose they used it because it was a quiet, out-of-the way spot high on a hill. The local suspicion was that the military brought people from other parts of the country, killed them, and then dumped them there. (Note: This information is verified in El Salvador Could Be Like That by Joseph B. Frazier. On p. 30 he reports that one person’s job was to do a body count. The usual number was six victims, but his record one day count was 47! Death-squad members would throw bodies off the cliff. They would land a few hundred feet down, becoming the problem of Panchimalco, a quiet indigenous village at the cliff’s base.) Now it has changed and is a breath-taking vista where vendors sell their foods and merchants sell crafts.

During the war we tried to stay inside as much as possible. My grandfather brought us food. There was a 6 P.M. curfew. Some days I needed to make a two-hour walk one way to Santiago Texacuango to buy materials for making the textiles. I never used main roads but went through fields and back roads.

At age nineteen I fell in love. He was not any man; he was a very special man. He was a musician who played saxophone in a Santa Tecla band. We lived together, and at 21 I had my first child. We had four children – three sons and one daughter. One of our sons inherited his father’s musical talent and also played saxophone. He was a very good son. But he died during the war. It is very painful for me to tell this. The army came one day and took two of our sons from our house and killed them. They were only 17 and 19 years old. Five other young men in our town were taken the same day. The army accused them of doing things they had not done. There was never any investigation of any of their deaths. It hurts to remember this because they were killed unjustly.

Losing my two sons and losing my grandma were the hardest times of my life. I didn’t have a strong bond with my own mother because she did not raise me so losing her was not as hard.

I have four grandchildren – 2 boys and 2 girls. I try to pass down some of the indigenous folk tales to them when I remember them. There is one about when the animals such as the hens disappear, the villagers blame the monkey as being the culprit; the villagers go find the monkey and set fire to it.

Claudia Vegas telling her story to Pastor Luis & Caroline Sheaffer

I see myself as a Pipil Indigenous person and try to carry on the traditions of the weaving through my craft. I teach classes here at this center four hours a day to both adults and to children. I enjoy teaching and have much patience. I began teaching here in 1978 to give my kids an education. My one daughter is a professional seamstress, and my son is a barber.

The director of this center takes me along with dancing groups into San Salvador and to other provinces across the country to demonstrate weaving at tourist expositions. We take our products along to sell. I enjoy that.

My life consists of work. That is all I’ve ever known. When I retire, I guess I will spend more time with my family.

Editor’s Note: At this point in our interview we are being surrounded by women who are visibly agitated. We ask our translator to find out what is wrong. It seems they have been waiting for Claudia’s weaving class to begin for over 30 minutes. They drove 1½ hours to attend it. We apologize for the scheduling conflict and quickly depart.

We will try to return to this picturesque little town famous for its colonial style church (over 200 years old) which we somehow missed altogether. The town is also known for its lavish celebrations around its patron saint day, May 1st, and around Easter when the people decorate with flowery palms and wear traditional colorful hand-woven textiles and observe traditional customs. Yes, we need to return.