During our last visit to El Salvador, we had no intention of interviewing anyone for stories. We had a dual purpose for this trip – to baptize the daughter of a scholarship student and to celebrate with some of the scholarship students we have supported for many years who were being ordained into the Lutheran ministry. The latter date was planned two years in advance. It was touch and go up to the day of our scheduled flight whether we would make it due to medical issues on both of our parts.

But we got on the plane delighted to be en-route with the attitude that IF we happened upon someone with a story to tell, we would take it, but we would not seek anyone out. However, when my partner disappears from sight for a period of time, I can generally predict what he is up to. Like a good detective or reporter, he has an uncanny knack of sensing someone in a crowd whose story needs telling. I marvel how some of our best stories come about in this very spontaneous, unscheduled way.

The first discovery was Tulio. Tulio has written his own bilingual book, and I have no need to re-write it; however, having read the copy he loaned me, I may later write an abbreviated adaptation of his story for the readers of this blog.

Like many survivors of the country’s civil war and refugee camps, Tulio witnessed horrific atrocities inflicted on his immediate family members which later resulted in a family diaspora as well as burning of his village. He broke down only once when talking about witnessing the rape and subsequent death of his younger sister whom he was extremely attached to.

His heavy story just goes from sad to sadder. Yet within it are places that made me smile and think, “Wow! How fast-thinking and clever.” I decided to share a couple with you, our readers.

The military annihilated Tulio’s family except for him and was determined to eliminate him as well. Through some clever shenanigans, though, he was able to outsmart them and escape.

It was on January 11, 1981, in Soyapango, when Tulio heard guns approaching in a supposed “safe house” where he was leading youth as an FLMN organizer. Knowing he had few choices to escape, he pretended to be a crazy, sick person aimlessly wandering around the facility hoping the soldiers would be uninterested in pursuing him. He was correct, and his quick-thinking ruse saved his life.

Another time he sensed an ambush was being set up for him while he and a comrade were traveling in a vehicle on a remote road. When the soldiers appeared, he was already disguised as a pregnant woman headed to the hospital for delivery. The bluff worked, and the soldiers allowed the two to quickly pass.

How anyone can survive psychologically and emotionally from these kinds of trauma and then go on to minister to the needs of the country that destroyed him challenges my comprehension. Yet he does just that. Today Tulio dedicates his life to fund-raising for CRECE, an organization to gather supplies into large shipping containers to send to poor communities in El Salvador to improve their standard of living. He travels from his home in the U.S. twice a year to distribute the supplies.

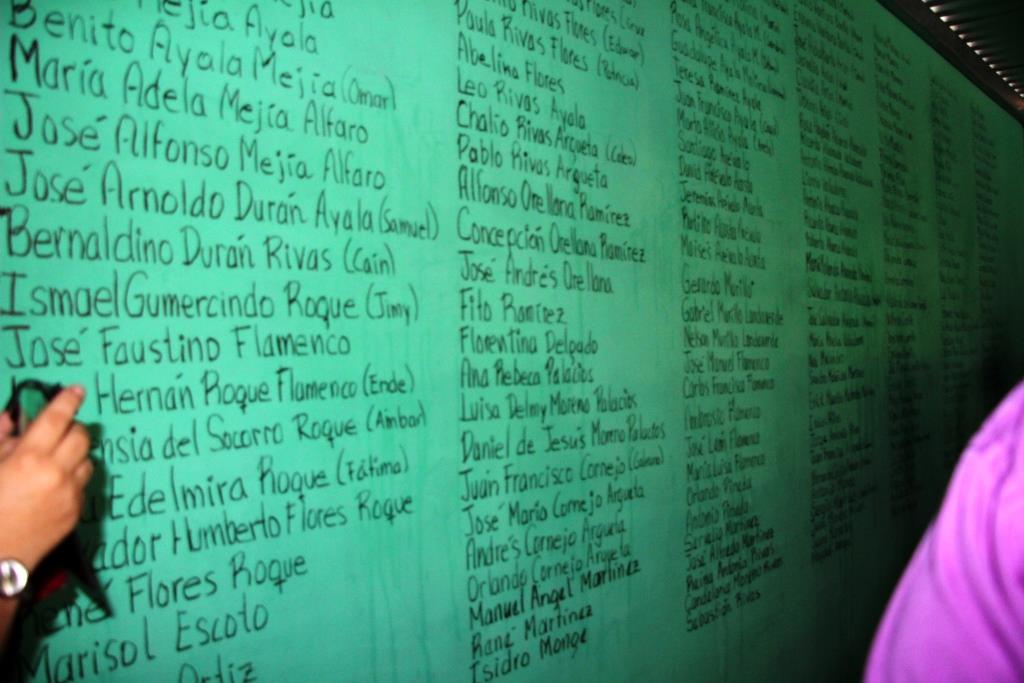

On another day of our visit that week, we attended a celebration at Fe y Esperanza, a former Lutheran refugee camp during the country’s civil war. That day of our visit a wall was being dedicated with names of hundreds of refugees who had lived there during those war years when it served as a refuge of protection for innocent villagers.

Among the many speakers the day of our visit to Fe y Esperanza was one of the survivors, Rosaura, who lived there as a young girl. She described being so weak from starvation and dehydration the day she arrived at the camp that she was unable to climb out of the back of the truck without assistance. She described how Bishop Medardo Gomez welcomed all the people with open arms and had a table full of fruit and hammocks ready for them. “The following day the military trucks came with soldiers carrying weapons pointed at us. I casually wandered to the front smiling, ‘Welcome. Are you here to visit us?’” Apparently, weapon-carrying soldiers are unaccustomed to greetings from friendly, young girls.

They then demanded, “Who is in charge here?!” Someone must have given Bishop Gomez’s name because the soldiers asked Rosaura where to find him. “Well, he’s probably in the church [in the city]” she responded, knowing full well he was there with them all along. Quickly the soldiers exited the camp and presumably headed into the city in search of the bishop. This young girl’s ruse probably saved the bishop as well as many other lives of the refugees at the camp that day.

Today Rosaura works to preserve the memories of the many hundreds of people who lived in that refugee camp. She wants that time in Salvadoran history to never be forgotten.

Both of these endangered people could have been shot and killed instantly in the blink of an eye. What gave them the courage to think up creative ways to outsmart their would-be assailants so quickly and effectively divert the fatal action of the soldiers? Was it bravery, courage, or divine intervention? Did miracles take place?

As I reflect about the stories they each shared, the miracle of their survivals didn’t end on a particular day of their clever ruses. The long-term miracles seem to be in how they each chose to live their lives after their trauma during the war. In each case, they live in humility and service rather than in bitterness and grudges. THAT takes commitment and courage!