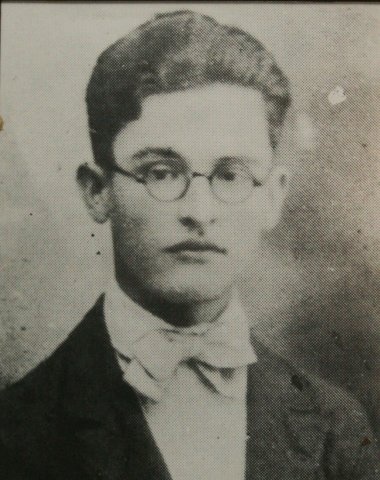

Story of Guillermo Joaquin Cuellar Barandiaran

“When reviewing all the country’s history as a social science over the last 500 years, it has been full of lies. That is a big disappointment to me.”

Editor’s Note: Even though we’ve heard him in concert many times and he immediately agreed to participate in our project several years ago, it is not easy trying to track down Guillermo for an interview. We seem to always be in opposite countries or continents. Today we were fortunate enough to connect with him right after he returned from Nicaragua.

Attending one of Guillermo’s concerts is more of a learning experience than simply entertainment. One quickly becomes caught up in the struggles of the Salvadorans as he personally gives testimony to his relationship with Archbishop Romero and how that impacted and inspired much of his music.

It’s fun to discover I’m woefully misinformed (ie. wrong) and today was one of those times. I had always associated Guillermo strictly as a professional musician. Today he underplayed that role and shared his relationships, philosophy, other careers and career choices, as well as future plans. I think he would have given us his entire day if we had realized this and budgeted our time accordingly.

Can you share your experience of living in New Jersey? Is that home?

No, I was born here in El Salvador on August 13, 1955. Although I had traveled outside the country to visit my uncle in Mexico for a month and a half when I was twelve, I never before visited a non-Spanish speaking country.

When I was 15, I was part of a group of 40 Central American exchange students to spend a year in the U. S. Collectively we represented Nicaragua, Mexico, and El Salvador. This was a big adventure during the time when it was expected that you dress up in a suit and tie to fly. We landed in New York City on a 747 jumbo jet during the Christmas season. Staying in the four star Tudor Hotel, watching ice skating, and attending the Christmas Scrooge show at Radio City Music Hall, was an overwhelming experience. It was like another time in space to me.

The adventure continued when I, knowing no English, was placed in a rural New Jersey home where my host family knew no Spanish. In fact, no one in the school spoke Spanish. Being a musician, I have a good ear for picking up languages. Everyone made efforts to help me, and the one tender moment I will never forget is during the daily Pledge of Allegiance when this one little black girl standing behind me began singing “Feliz Navidad.” That was her gift of trying to connect with me.

The experiences of that year were wonderful and enriched me in many ways. After the assassination of Monsignor Romero when I had to flee to Canada and Europe, I was blessed to have learned English that year not only for basics such as ordering food, but also because English is the language used within the church.

Was your family a family of means?

My dad had studied medicine and made his career as a pharmaceutical representative. My parents were able to financially support me through my university studies. This included providing me with the resources for that trip to the U.S. when I was 15.

After graduation from university, because of my close association with Monsignor Romero having been a member of his staff, it was too dangerous to remain in El Salvador. A combination of churches, organizations who invited us, and my own finances supported the necessary travel needs.

When did you first meet Monsignor Romero? What was your impression of him?

In 1976, when Romero was a bishop and I was a 21-year-old in a youth Catholic pastoral group, we wanted to have a youth encounter and needed to coordinate details with him. He graciously offered us the use of a house on a coffee finca in Santiago de Maria for two or three days. (The owners there made it available for his use.)

Imagine the persona Bishop Romero elicited dressed conservatively in his full-length pitch black cassock wearing his over-sized cross. From a distance he appeared larger than life, and too formal to be approachable. Yet, when you got near him, he was the most soft-spoken, gentle man you could imagine. This created a dual impression when you met him for the first time.

As you were leading this group of youth, were you feeling a call to the priesthood?

I had studied the Christian movement and its music during high school when I was 16 and 17. After high school I had a strong religious conviction and wanted to become a priest. Another friend and I had an interchange and blending to enforce our choices, so we studied philosophy at age 18, knowing that if I attended Jesuit school, I would need to study philosophy. I continued to study at the Jesuit university, UCA, until I was 23 and eventually declined the option to become a priest. Even though I didn’t pursue these careers, I never regret the intellectual stimulation I received there because I am able to reflect on a wide range of all types of thinkers that I studied which has been a treasure to me.

What direction did you turn your attention to studying when you realized the priesthood was not your calling?

I stayed within UCA where I could continue to express my spirituality, but introspectively I was beginning to recognize and to affirm my musical talents. Through gaining the intellectual structure, I now needed a way to express my spirituality. I felt I could do this through music. A magnet was pulling me in that direction.

This was an internal struggle as my spirituality was growing as well as allying myself to the bishop.

Were you aware that relationship with Bishop Romero would take you onto a dangerous path?

On a conscious level maybe I was unaware and felt somehow protected or was undeterred by the danger. There was no doubt that I needed to continue, however.

How did your parents feel about your decisions?

My parents came to support my life decisions regarding careers, need to leave the country because of my relationship with the bishop and subsequent danger that posed. I believe it may have been somewhat harder for my dad than my mom. I know it required a great deal of effort on their part to understand at times, and my sisters and I have a lot of gratitude for that. My parents questioned us at times but never discouraged our decisions.

My dad told me he would pay for my university expenses even though he felt the philosophy major was not one that would offer me a suitable career in terms of making money.

How did you combine to express your internal spirituality with your music?

My musical compositions are mostly from the point of view of God. I write about issues I feel that God wouldn’t like about our human relationships such as indignities, and injustices to one another. Many people have told me “You talk with presence.” I feel I have to be more or less like the prophet Jeremiah saying that I don’t want to speak about these things. People frequently request copies of lyrics to my songs to be reminded of the issues I am addressing in them.

I have never viewed music as a profession because I always see it as an expression of society or the Spirit. It was never a feeling that I needed to improve my musical skills or get more training for a career.

Once Bishop Romero became Archbishop Romero, what changes did you observe in him?

In just that one year’s time, 1977, I heard and observed a very different man. Now instead of my asking HIM for assistance, he was asking ME for assistance. He addressed us students at the UCA, “Please, I need your help.” My response was, “I’m a musician” to which he suggested, “ Please, you can work at the radio station.” I was 22 years old, and I was surprised that he was sincerely asking for help. In my heart I felt compassion for him and felt suddenly tiny. But he had a mission and could not do it alone, and I was willing to do anything to help him in that mission. I worked at the radio station up until the time he was killed.

How did your personal situation change after Archbishop Romero’s assassination?

At first I wasn’t aware of the whole picture regarding his situation and how it would ultimately affect me. The system of military repression was so sophisticated. I experienced capture by the National Police in 1978 and again in 1979. In 1978 I was held for four or five days. The second time the police were seeking information from inside the church. The strongest word for them was cathechist – one who teaches children the doctrines of the church. This person was considered to be an enemy. The police wanted to know names of my teachers within the church. They wanted information on Romero and began pulling other friends of mine out also. I was probably going to end up disappeared like so many others.

How did you react to those imprisonments and threats?

A friend of mine from Nicaragua encouraged me to come to Managua under the guise that there were resources for a record deal. I was looking for that opportunity and financial support, and he was extending that to me while I was saying “No, I don’t have time.” He offered a 2nd, a 3rd, a 4th, and finally on his insistent 5th offer, he said, “Let me put a friend of yours on the phone.” Paulino Espinoza was more convincing and I trusted him so in 1980 I told my wife, “I’m going to Managua for a week or two.” I returned 13 years later.

Did you stay there alone the whole time?

No, my wife and our first daughter joined me three or four months later. We went to Mexico in 1983, and I returned alone to El Salvador to work as a volunteer with the underground for the FMLN in a mountain radio station in Chalatenango. (The guerrillas had two radio stations in operation.) I worked there for three years as a Christian quoting the Bible. Like all members of the guerrilla, we never used our real names, and the one I chose was Romero’s middle name, Arnulfo. On a personal note, this was great for my physical health because I lost 50 kilos and became strong. [He shares this laughingly but seriously.]

Those in charge of the radio station offered me a rest, so when a musical group came to the camp offering me a chance to join them on international festivals, I agreed. We performed in places like Moscow, Columbia, Peru, and Germany. This tour had run its course and I was now ready to move on in my life.

Then where did you live?

At that point I returned to Managua, Nicaragua, to live with my second wife and second daughter. I recovered my links within the church movement there and was asked to fulfill some roles and continued singing for financial support. I was able to remain in solidarity with El Salvador and once again returned to live here after the 1992 Peace Accords.

Your family is international.

Yes, I keep my links and am grateful that my three children love me and are not resentful of the fact I wasn’t with them when they were growing up. My son lives in Vancouver, where he was born in 1982. My one daughter lives in Managua, and I visit her whenever I can. I have a wonderful relationship with all my children. I treasure the time we spend together and consider my children my greatest success. They have helped me understand that they are the persons they are, in large part, because of me.

And after those 13 years?

In 2000 I was drawn to the study of social anthropology as a career. As the new government was beginning, a friend of mine who was Secretary of Culture invited me to work here in this department. I spoke with my musician friend, Paulino, and explained that I had this opportunity I wanted to pursue.

For two years I’ve been working to research social issues here in the Social Ministry Department of the cultural center. My role is being a member of the government office dealing with social and cultural issues.

In addition, I teach classes at the Universidad Francisco Gavidia in social anthropology, cultural anthropology, Meso-American struggles, and indigenous culture. My courses run three days a week from 6-7:30 A.M. (Surprisingly, the students do not complain about those early hours because they want the class.) I eat breakfast and then come here to the office at 8:30 A.M. for a full day of work.

You said it’s never been about your music, yet you are well known for composing two masses – “Misa Popular Salvadorena” in 1980, and “Misa Mesoamericana” in 1994 as well as many popular hymns including “Santo, Santo” and “Let Us Come to the Banquet” used not only in Roman Catholic liturgy, but also in many ecumenical worship services.

Archbishop Romero commissioned me to write the first “Misa” (mass) and to know how popular these songs have become is fulfilling. Working with Paulino and that group for thirteen years, I felt that I paid a kind of a debt to my country because I left during the war which I was now able to repay. I owed my country in this chapter of my life, and now I feel I fulfilled that debt. It nearly provided me with a way of life.

How do you still have time to perform your music?

I still sing, doing gigs, when requested. Recently I have been to Iowa, California, and Pennsylvania.

Do you still compose music?

Yes. My last effort was based on a special friend, Magdalena Enriquez, during our times within a Christian-based community. [Maria Magdelana Enriquez was a human rights’ activist who was kidnapped at her front door in front of family members including her child and later brutally assassinated on October 3, 1980.] My song is about how she was captured, disappeared, and killed. But in my song she does not die. This is unnecessary for the music because she was martyred in real life. Instead the music pays tribute to her life.

When you compose, which comes first – the lyrics or the music?

It varies; sometimes they come simultaneously such as the one I have prepared for Romero’s canonization. Some of the lyrics include: “I will tell you miracles he performed . . .Now I ask you to perform miracles . . .follow the way of Romero.”

Can you share how the Salvadoran poet, Alfredo Espino, inspired you to compose?

I had studied Espino’s 96 poems in school, had compassion for this tragic poet who took his life at age 28, and felt I understood the genius he was. He was born in the wrong place in the wrong time. He had an empathy for those who are passionate for their causes. It’s a wisdom of the heart.

After the war I saw the country so destroyed of nature. Espino’s poetry such as “The Nest” so vividly described nature. Even though he wrote in the early 1900’s, I felt I could link his poetry with a new generation. In 2000 I wrote “Dos Alas” to convey this.

Are there other poets or artists you are drawn to?

Currently I have a relationship with a companion who is a poet and artist. (COULD THIS POSSIBLY BE DONNA PENA?) We are at another level of our lives. I am now 57 and she is 49 so it is a totally different experience. I am a very happy person who appreciates all the gifts life has given me.

What, if any, things would you do differently if given a chance?

If circumstances had allowed and life had not become so chaotic requiring quick decisions and death had not come when it did, I would have somehow found strength to engage in more deep and meaningful conversation with my father. This may have resulted in having had a closer relationship with him.

Do you have an interest in the free trade agreements with the U.S.?

Economics is an area ruled and influenced by a few people which I cannot impact. I choose not to put my energy into an area I cannot be effective in, so dedicate my energies elsewhere.

While studying anthropology, what has been your biggest disappointment in El Salvador’s history?

When reviewing all the country’s history as a social science over the last 500 years, it has been full of lies. That is a big disappointment to me. I now have more skills and instruments to help me understand. How can we have accepted the inaccurate history that was taught to us? It makes me angry and disappoints me.

What are you doing to share that knowledge with your students and others?

It’s a matter of discovering that what we’ve been taught has been deceptive, and now it is difficult to know what direction to take with this information. I’m planning several things. I’m trying to expose it by teaching and by writing articles and a book. I plan to make a movie which will appeal to a wider audience. By working within this capacity in this office in the Ministry of Culture I have more opportunities and resources available to put my knowledge and creativity into action. I want the next generation to grow up knowing the truth.

The problem is always in the heart of the human leaving the impression that we are abandoned. We grew up thinking one thing and now we have to re-discover we’re not abandoned so we have to take positions in life. The secret to resolve that is always inside the heart, not outside. It is within the community to endorse and support it also.

What is your hope for your country?

My dream extends beyond my own country; it is for humankind. It is that as human beings we could understand we are not alone within ourselves. All the energy we need to survive is already a gift that we have had since we were born.

Is that God’s grace?

In the same sense that it’s free and you cannot control it. You just need to recognize it, and you are ready to do many things.

How would you characterize your faith now?

In the last five years I’ve been in dialogue together with three viewpoints – Christians, Buddhists, and indigenous Native Indians. The blending of these three spiritual wisdoms is what I am finding meaningful to me. Last week I led a collective worship in Managua, Nicaragua, in the blending of the prophesies of the Bible, the Buddhist worship, and the indigenous spiritual readings. They are all the same in the simple and in the deep. To have connected with these other viewpoints in the past five or six years has been a great joy. It gives me more desire to study, read more, learn more, and find more ideas of interest.

I am proud to be a Christian, but I do not consider myself in the Catholic Church. I understand better, but the Vatican religion has been a lie since the beginning which I call the Vatican Christianity. I let the gospel guide my Christianity and feel connected in my mind and heart. For me, teaching only one religion is wrong. My hope for humanity is that it’s not this or that, but we can at last understand the future is blended together.

Editor’s Note:

Today’s interview was so multi-faceted covering such a wide range of topics that I left with my head spinning. I am in amazement of how this one energetic, talented middle-aged man has enough myriad projects to accomplish that you would think he is eighteen years old. What is even more endearing is his open-mindedness and yearning to continue to learn and grow. And now that there is a Latin American Pope in office, Guillermo is already one step ahead with his song composed for the day that Pope Francis declares Oscar Romero canonized.