“I Was Involved in Working to Change the Story of My People and My Country.”

You will not find the name Damian Alegria on my birth certificate. I have been known by numerous names–even at the same time. During the war when I worked in the mountains as an FLMN guerilla, it was necessary to have several names at the same time. I used different names with different groups as protection in case someone in a particular group was captured and tortured for information. If he gave a name by which he knew you yet another person gave a different name for you, it helped to avoid discovery by the army. My given name is actually Jose Mauricio Rivera. In the mountains I mostly went by a single name, Damian. I was encouraged to add a surname when going to receive United Nations representatives who came to ask if we knew about peace negotiation. While I was walking along to that meeting, I was considering what I might choose, I decided to add the word that meant the reason we were fighting. We were fighting for a dream of “happiness in the people.” The word Alegria literally means “joy.” I used this name with the media because it struck a cord with them and later proved important in forming a relationship with them as they came to my defense against the military dictatorship. The name was a good fit, and after the war I legalized my name in its present form.

Standing up for what I see as right may be a hereditary trait. In 1957 when I was born, El Salvador was extremely oppressive and patriarchal. Women were not even encouraged to receive an education. My mother grew up on a coffee plantation in the country and secretly visited a teacher begging her to learn to read and write. She was being pressured to marry a man she did not love and consequently ran away from home into the city San Salvador to avoid this marriage. She did whatever job she could in order to survive. When I was born to a father who was the popular restaurant owner serving the president’s house, his parents offered to raise me if my mother would disappear. Although this would have been easier for her, she would not agree to these terms and left for another city. I was six months old at the time. Later when I was a teenager, I had the need to meet my biological father. He genuinely felt bad about what had happened, but by this time had married and had a family. It was an awkward situation, and I chose not to return.

I worked with my mother in whatever job she had at the time, whether it was harvesting coffee beans during Harvest Break at school in November and December or selling fruits at market. She taught me a valuable life lesson: when making a decision, stick by it and work hard to maintain it. My mother never married. She told me after the sixth grade it would be difficult for her to totally support my education, but she would help partially as her income would allow. I worked nights and attended school during the day to help because I wanted to continue my studies. I finished technical school in 1978. In 1979 I began at the National University. I was studying to be an engineer.

There were three key events in my life that were life-changing and calls to action which had a big impact on my life. The first happened when I was eight or nine years old. I accompanied my mother to a hunger strike of teachers and laborers demanding better salaries and better treatment. I asked my mother what they were doing, and her explanation was, “They are trying to have more food for their families.” Later I discovered that some of those people had been shot and killed, and I felt strange and questioned the motive. Growing up under a military dictatorship, I learned quickly to be careful and wary around the policemen and military because they were bad people.

The second event greatly impacted me because it involved such a basic human need and right: food. There was a similar hunger strike that occurred near my school when I was a teenager. Because I was now older, I could take part. I got involved this time by asking my friends to raise money for the participants and asked what else we could do. They requested that we get them some food. When we went to the market asking for food for the strikers and their families and then met as a group, a policeman approached us asking whose permission we had for this and began to threaten us. Because one of our teachers was a local mayor, we approached him for written permission. He reluctantly gave it but warned us to be very careful and not let it happen again or we may be punished. This written permission may have saved us from the grasp of the authorities and ultimately, our lives.

In 1977 when I was 20 years old nearing the end of my engineering training in technical school, I passed Freedom Square daily. One day there was a huge crowd, maybe 10-20,000 people gathered. They said there had been an election and the people had elected a candidate but the government would not accept the results of that election. They claimed the winner was another person. Election fraud was apparently common, but it was new to me. Late at night on February 28, I was awakened by bombs and loudspeakers in the streets. In the morning I ran to the square where soldiers and firemen were flushing blood in the streets. At that moment as I put the events together in my mind, I knew I hated the army because they were doing bad things to the people.

Someone asked if I would like to attend a meeting to do something about what was happening. This is something I was waiting for and I went. The person leading the meeting told me he was glad I came. He disagreed with what the government was doing and something needed to be done. However, the government was very strong, had weapons, police, and an army, and “we have nothing but truth and justice in our hands.” He made it clear that although he would be happy for me to join this resistance and be part of this revolution, it would be very risky. He gave me time to decide.

It was clear that the government would continue to practice oppression of the people desiring their submission and acceptance of whatever position the government wished unless things were forced to change. I wanted to be part of the change. It took great courage on the part of those who joined this revolutionary movement. It was important to do something. Life needed to have a goal, and that was to improve society. It would be a big sacrifice.

We didn’t go about it abruptly or aggressively. We were very purposeful, studious, and cautious. First we were taught about history, government, theory, and practice. We were taught what democracy meant, but not democracy in terms of how it is modeled in other countries, rather democracy in terms of freedom of choice for the people involved. It was more a feeling of democracy as an internal process. I read extensively during this time of consideration. Once I decided to be part of this movement, we were instructed not to tell anyone so that they would not be put in danger themselves. I did not even tell my mother for several years in order to keep her safe.

My actual responsibilities during the war began when I was proposed to build a network of communications for the organization including radio stations with electronic equipment as well an in the encryption process of inventing and creating codes. My engineering background was quite valuable in this work, and my friends felt I was well-suited for it.

Results of the war hinged on communications and the radio in particular.

One of my first assignments was to take control of the government-controlled radio stations to broadcast a message of hope to the people. I made the personal choice not to carry a gun which was a respected choice among our organization and not an uncommon decision. I did build a fake bomb, consisting of a sand-filled can with wires sticking out of it, which I held in front of me as I entered the radio station. As soon as we got inside, the operators immediately assumed the position of face-down on the floor. The “bomb” was a scare tactic to hold the operators at bay long enough to announce our message. It was fortunately a successful mission. Later I took a risk in sneaking back to a distant vantage point where I could view the bomb squad dismantling our “bomb.” We heard the police remark, “Those guerrillas are smart” .

Religion was not a strong influence in my childhood because my mother was busy being a single parent, which meant working to support us. When she wasn’t working, she was visiting people. I don’t remember attending church regularly. I had bad feelings about religion at that time. Priests were telling their people that their poor conditions were the “Will of God”.

At about the same time I was getting involved in the revolutionary movement, I heard about the stirring event that pushed Oscar Romero into action. That was the senseless assassination of his dear friend Father Rutilio Grande in 1977. When Romero was named archbishop in 1980, I understood that he wanted to be a different kind of religious leader. Monsignor Romero was denouncing injustice and talked about things that were happening publicly on the radio. My mother went to hear him every week. Being part of the organization I was involved with, we were discouraged from being in public places where spies were all around so I never went but I listened to him on the radio. (You could actually be killed for listening to his radio broadcasts in some areas).

I was near artists and musicians who thought we should go speak to Romero. He had been nominated for the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize but did not wish to go. We arranged to talk with him and tried to persuade him. He said prizes were not important to him; what was important was to work with his people who were suffering. We told him if he would accept, he would have a bigger audience, make his work more public, gain acceptance by the people on a larger scale, and make the government respect him. We knew the government was threatening his life. He said this was helpful and gave us hope.

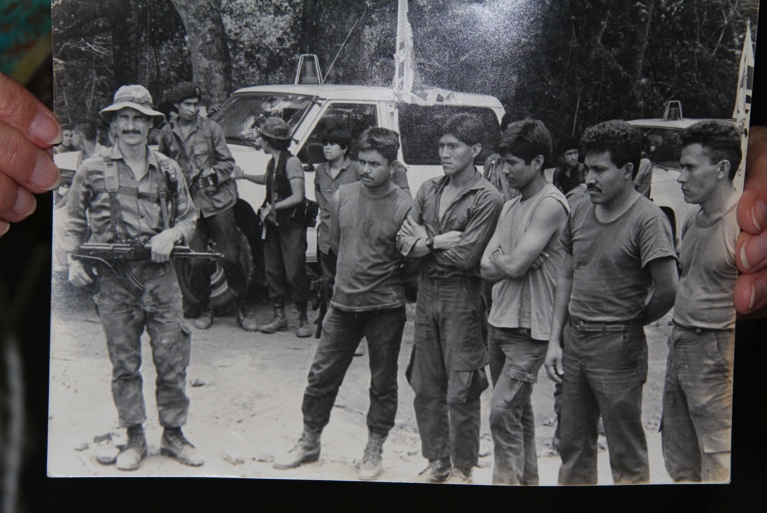

Damian on the left with captives.

Part of our guerilla training was to be prepared for capture, imprisonment, and torture and how to resist and survive it. I knew the treatment in prisons was much worse for guerillas than the average citizen. The possibilities of capture were strong and I felt prepared. I was captured and imprisoned three times during the war. In October, 1981, I made a crucial error. Although I knew that in the event I ended up using someone else’s vehicle, I needed to have memorized all the data associated with it, I got caught at a checkpoint in an unfamiliar vehicle without having done so. Quickly I grabbed the registration card and memorized the name of the owner, but I couldn’t see the address fast enough before I was stopped. My plan to avoid being detained did not work out, and the worst part was that I realized I was carrying revealing information on a slip of paper in my pocket that would identify me as a guerilla. I stuck it into my mouth and tried to swallow it, but the policeman made me remove it. Fortunately it was illegible by that point and did him no good. I was put into prison and tortured but was freed by friends who arranged for my release by a lawyer. I was considered a simple thief. I returned to the mountains for three years. Later I was sent back into the city for 1 1/2 years to help re-build the organization due to so many of our group being captured. We had a strong presence in the capital. This was 1984 or ‘85.

By the two subsequent captures, I was known as a guerilla. We were trying to double up our numbers outside the cities in order to keep the armies from taking over the land owned by the peasant workers. (Many of those hard-working laborers had joined our movement. By day they worked their land; by night they were actively involved in the movement fighting against the government totally unsuspecting to the officials.) During the second imprisonment, besides physical torture, there was ten days of sleep deprivation. I gave them no information because of my commitment to our cause. They released me to my friends to kill me, assuming because I had been released, they would think I had been a snitch. However, I explained everything, and they knew I had not betrayed them. They trusted that I had remained silent. I stayed with a small group in the mountains for another three years.

Then I was sent to the south side of the city where there is no cover of the mountains in the back as in the north of the city. A group of friends was awaiting instruction in a house. I went to warn them to get out, but it was too late. On Dec. 11, 1989, we were all captured. The torture was administered by military trained by North American forces. They used very cruel techniques. In addition, they were spreading deceitful lies that we had killed the Jesuit priests, which was absolutely false. On December 24 we were sent to a penitentiary with many political prisoners. Inside we were actually able to make strong political plans during the three months I was there.

When I was released, I returned to the mountains and became a spokesman for the guerilla movement with the journalists. I invited them to come live with us to get first-hand knowledge of how we lived and what we were about. This was now 1991. The news media helped us a great deal. Our emotions were up and down depending on what we heard about possible peace accords. Sometimes we thought it was over and peace was imminent; other times we thought there may be another ten, twenty, or thirty years of war ahead. But we made a pact that we would continue for the duration, even if we personally lost our lives. At least it meant I was involved in working to change the story of my people and my country.

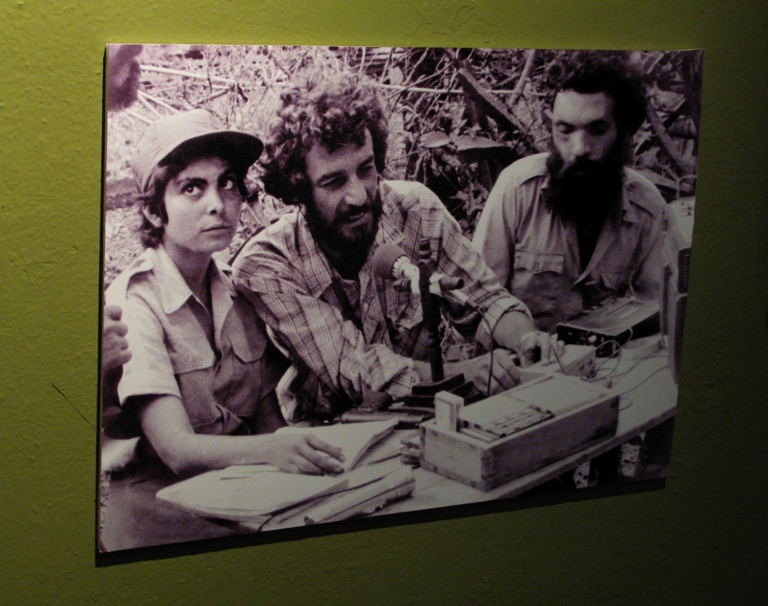

Damian & Carolina

In 1989 I met Carolina. Like so many families, she was among those who had been expelled from her land as a child and sent to a refugee center. A Jesuit priest by the name of Jon Cortina, served her refugee center faithfully. Carolina was impressed by his work as well as by him personally. He influenced her into considering the call to become a Catholic nun. At one point she visited her family and was captured and imprisoned. After her release, she went to the mountains to work for the rights of the people. That is where we met. Love prevailed over the call for the church. As an aside, Carolina and I remain strongly committed to an organization that Father Cortina is associated with which involves children stolen during the war. The group is searching for 800 stolen children. Only 300 have been found. The name of the organization is Asociacion Pro Busqueda de Ninos y Ninas, or Pro Busqueda (http://www.probusqueda.org.sv/) This is a Spanish site.

We were eagerly awaiting the peace agreement despite the feelings some people had that the guerillas were happy to be at war; this was not the case at all. The United Nations forces approached the guerillas to ask if we were in agreement with the peace accords to make sure all groups would agree that we would stop fighting. In December 1991, the FLMN signed a cease-fire agreement. The government did the same thing. It was a nice celebration for Christmas.

After the war I returned with a pregnant wife, Carolina, ready to begin a new life. It was very difficult; although I had been an engineer, it was not possible to get a job with the government or a business. I had to find a way to survive. A friend had stayed with us and thought our hospitality could be made into an enterprise. We started a business out of our home to accommodate those guests who are in solidarity with us Salvadorans. We call it the Hotel Oasis. Our original thought was to do this only until Carolina would finish her degree in business administration at the university and I would finish mine in economics. But we find this is something we enjoy and makes us happy. We don’t do it to be rich, but we make enough to live and educate our two sons.

In addition, I own and operate a radio station because of my link to communications during the war. I was recently elected to the Congress, National Assembly, as of January 2009, serving a three-year term. I now have a solid voice in government decision-making, which is respected. This involves re-building and coordination of the country. There are many issues that need major change in our government. Privatization of resources is one of them. There are good intentions to provide land to the poor people, for example, but much needs to be worked out. We need to help people lose fear of the FLMN, which some still see as radicals seeking to destroy the government. The reputation is still based on misinformation from during the war. We seek to be more aligned with other governments in Central America and become more united with them. This is perceived to be a threat by the U.S. The fact that many multinational companies send their profits directly back to the U.S. does not help the people here in El Salvador. We don’t want this anymore. There are many campaigns against this practice. We are learning a lesson that we need to have a better life together. This means to get away from U.S. and European dependency and concentrate on building our relationship with our Latin American neighbors whose culture and history we share.

[Editor’s Note: This unassuming, quiet man, Damian, has worked tirelessly for the voice he now holds as an elected official in his government. He is a bit of an entrepreneur, a family man, and a benefactor to an organization for missing children. Damian has had many names. He also has many gifts, interests, and abilities.

Damian and Carolina are friendly, trustworthy, reliable, and gracious hosts of the Hotel Oasis in San Salvador. They, or members of their staff, personally welcome you as you come and go every single time throughout the day. As I departed this past time, Carolina hugged me and said, “When you are in my country, consider this your home”.

Check their website for more information: www.oasis.com.sv

Let Freedom Ring For All The People