Alfredo Chavarria

“When you have seen injustice with your own eyes and you have seen repression with your own eyes and listened to Romero’s homilies . . .

Esta historia se escribe en Español = This story is also written in Spanish here.

(Alfredo uses Erick as much as his given name because Erick was his war name taken at age 13 when he joined the guerrilla movement of the civil war)

Editor’s Note: If I were asked to summarize Erick’s life in a single word, it would be the Spanish word, consciencia. This word epitomizes his ideology from the time he was a young boy and continues to motivate him even today at age 47.

Consciencia – This is the word that everyone associated with the guerrilla movement used to describe the awakening within that drove them toward a force greater than themselves individually or their family. This consciousness was the realization that conditions and human rights needed to improve for everyone, not just the wealthy.

I was the oldest child born February 16, 1967, into a large family living in extreme poverty in Chalatenango Department. Since our dad earned too little to provide for our family’s needs, our mom needed to help support us. She was often absent from our home buying or selling items such as chickens in order to supplement the family income.

Beginning at age six or seven, my role was to care for my younger brothers. Our oldest sister cared for the younger sisters. I accepted my role and didn’t really think about the responsibilities involved at the time. In retrospect, I realize I really had no childhood of my own. I never had any toys nor went to a park to play. We each had to work to survive, and for me that meant going to the forest to gather roots to eat, making the tortillas when our mother was not there to do it, and mixing water with sugar to feed the crying babies because there was no milk.

When our parents cut sugar cane or harvested coffee, all we kids went along, and we older ones helped while looking after the younger ones by putting down towels or hanging hammocks to keep them contained, safe, and out of the way. A working day was typically 8 AM to 4 PM, and we each received one tortilla with beans a day and each earned one colon per day in wages, amounting to seven or eight colones salary for an entire family. (This is less than $1 per day.)

The campesinos owned no land and had no rights. As campesino workers employed by wealthy landowners, we were aware of the injustices of the workers because we lived them. After the Catholic Church’s liberation theology became popular in the country, more people became aware of the exploitation of us campesino workers. Workers began to demand better salaries and better treatment. To protest these conditions my family stopped cutting sugar cane and harvesting coffee in 1975.

My mother organized others for better life conditions, better treatment and rights and then incorporated into the war in 1977.

The government retaliated by organizing repressions against us. Our response to these repressions was to organize ourselves. Our mom actively advocated, and she inspired the rest of our family to get involved to seek a changed and better system. We knew we had to be part of it. When you have seen injustice with your own eyes and repression with your own eyes and listened to Romero’s homilies, you grow up with revenge inside. Romero had filled us with strength to fight for something better and fought for the people of the country. He told the truth despite whom he had to talk against: the soldiers, the rich, those in power. He was our example.

When the military burst into our home suddenly, my mother and I quickly ran away, leaving the younger children behind. There was no time to think of consequences; we had to run. At that time in the war, the adults were more at risk of physical danger than the young children. Later on, however, even the little ones would have been killed when the cruel soldiers later adopted the same cold-blooded practices as used during the Viet Nam war: leave no witnesses behind. To their horror, the younger kids witnessed the military killing family members in front of their eyes in our home.

At age 15 I joined the revolutionary forces fighting first in Chalatenango, then in Cuscatlan, Cabanas, the volcano region of San Salvador, working in many operations. I was in charge of a group of eight men.

Our ideology was looking beyond our own needs or even our family unit. Our ideology was for a much larger cause. Conditions needed to improve for everyone. All people needed to have the same rights and opportunities.

There were several times I was wounded during the war and am lucky to be alive. (Erick shows us his various scars leaving us to gasp in unison.) In 1984 our unit was following soldiers of an Atlacatl battalion (the counter-insurgency group associated with massacres later investigated for war crimes and forced to disband after Peace Accords) when the soldiers placed a land mine in the area. I was in the front, and its shrapnel wounded my neck, back, and left arm.

Hesitantly and humbly, Alfredo revealed a few of his war wounds.

The following year, in 1985, in Guazapa, soldiers were planning a massacre. We fought for six months with action every day, eating only one tortilla each night because of the heavy action during the days. Confusion about who were soldiers and who were guerrillas was followed by a volley of grenades that killed three of my companions and wounded two others, including me. I was unable to stand because my legs were badly wounded, so I crawled by pulling myself with my arms. Soldiers were following close behind us. We needed to hide all night, and during that time my wounds became badly infected with worms. At 5 AM the next day we made it to the river, and two hours later the guerrillas discovered us. Two days later they took me to the camp, and at midnight looked at my wounds and found worms in every crevice of my body; however, it was too late at night to deal with them, so they put tape across each wound to try to suffocate the worms. As the worms began to suffocate, they bit more of my flesh, it was so painful I could not endure the pain and ripped off the tape.

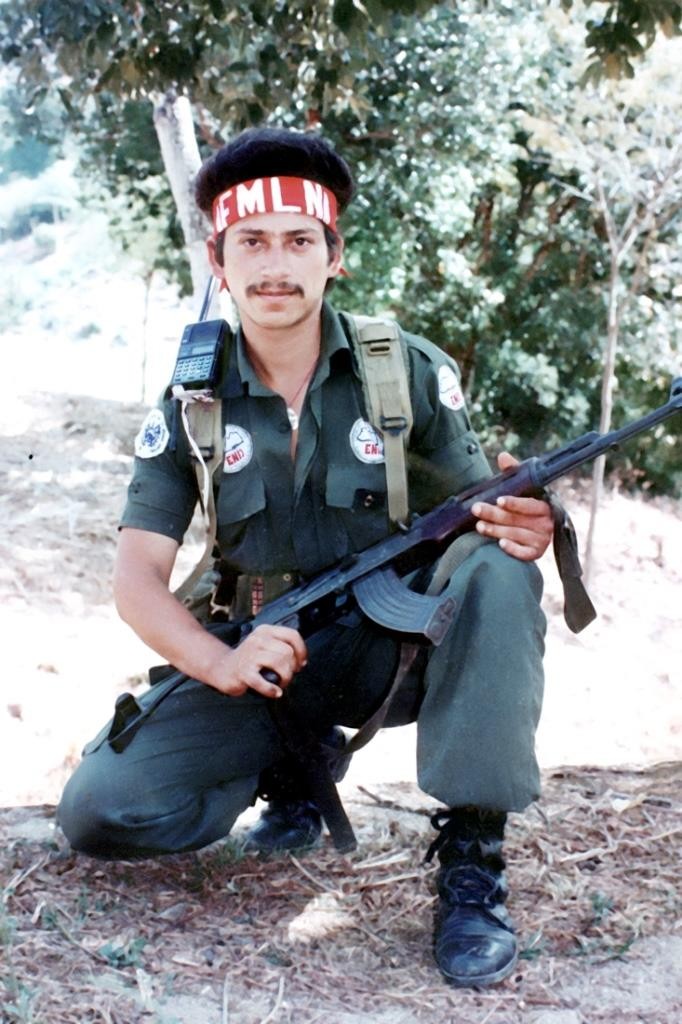

Alfredo as a young man.

At 7 AM the enemy was only 1 km away, and I shouted because the anesthesia they were using was ineffective. Several people were taking scissors to cut away all the infected tissues throughout my body. They treated me with antibiotics and put a blanket over my mouth to keep me from revealing our location to the enemy. To this day my one Achilles tendon remains damaged, and one foot is shorter than the other due to it being cut. I now walk with a limp.

The third event occurred in 1987 at a big base near the hydroelectric plant in Cabanas Department, Presa Cerren Grande. This is a large lake which was under attack. I received a stomach wound and needed to walk alone from 1-5 AM with a bullet inside me. There under a mango tree two volunteer doctors, one from Italy and one from Mexico, operated on me without anesthesia. This required a six- month recuperation period before I could re-join my group.

During that recovery time a companion taught me how to read, write, and do basic math. As a kid I never had the opportunity to attend school, so this was a chance to learn some of the skills I had missed.

Our ideology was to continue to fight for the duration of the war. We were totally invested in its cause. During that time some of our family had gone to Mesa Grande Refugee Camp across the border in Honduras. On occasion, if I got a day free from fighting, I would go visit them, but that was rare. I was just relieved knowing they were safe there. It was not necessarily a good, nurturing environment. However, with all the international presence and support, I felt they were safe from massacres.

There were also joys during the war. After successfully attacking a military base and avoiding casualties, we celebrated in small ways such as listening to a radio broadcast under a tree or along a river. It was our simple attempt to have a small party. At Christmas or New Year’s we celebrated by buying a chicken or maybe a cow to have actual meat as long as there was no risk of soldiers close by or bombing. Sometimes during the war Catholic priests or Lutheran pastors would lead worship services, which was another joy. They supported our efforts.

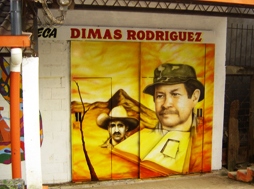

Prior to the Jesuit priests being killed (11/16/89), we guerrilla troops were prepared to take an offensive to the capital. 5,000 troops were already at the San Salvador volcano. Then negotiations stopped. The general of the guerrillas said, “Call them to come to the capital to show the government the power is what we said it was.” I had the opportunity to go along with General Dimas Rodriquez. He had the opportunity to intercept the troops on the radio. He was a good brave man. He was killed during the offensive. They say the good leaders always die because they always lead by example by being in the front of their lines. I learned a lot from him. He didn’t care about his own life; instead, he cared for the whole country. We retired from our post at the volcano.

My 13-year old brother, who was also fighting, was lost and afraid at that location. I found him and encouraged him to obey his orders. We were proud of all of our siblings who were involved in the movement. Life in the guerrillas ended in 1992 with shouts of joy when the Peace Accords were signed. We heard the news on the radio broadcast from New York and then officially from Mexico, where the agreement was formally signed. I remained in the guerrilla camp one full year after that to make sure the peace process was followed up.

I met and fell in love with a woman named Cruz in the front lines in 1988. We remain together and have three children whose names are Oscar Alfredo, Anna Elizabeth, and David Rigoberto. (His first name is Cruz’ brother who died in the war and middle name is my brother who also died in the war.) They are all in their mid-twenties now.

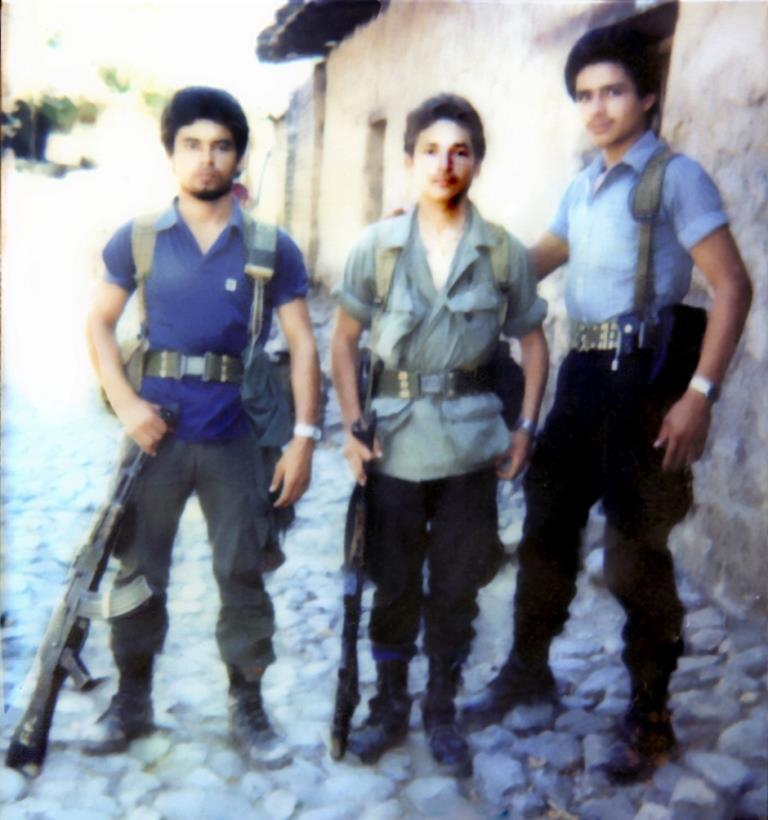

Alfredo’s brother, Rigoberto, in the middle was killed during the war.

Some changes have occurred as a result of the war, but there is still a long way to go. The state has a big debt to pay both groups, the military and the guerrilla forces, for all the trauma, psychological, economic, and health issues incurred from the war. I am not satisfied that after 12 years of fighting we didn’t get support for things like our children’s education. We still have to work as hard now as we did before the war to provide them with opportunities. The same is true for the military. This is also true of pensions. Only a very few veterans receive lifelong pensions. Mine and most others were one-time, lump sum payments which was a minimal stipend.

During the war when I would look up and see those A-37s flying over, it was my dream that when the war ended, I would become an air force pilot. It was alluring to think of defending my country. However, we guerrillas did not win the war. Plus without veteran financial assistance for education, I could not possibly afford a career that expensive.

In the previous administration I worked with the vice minister. I have moved through the state system in the country and now serve as a bodyguard for prominent officials. Currently I am assigned to protect Italy’s ambassador. I do not belong to any one party.

Coming out of the intensity of a 12-year war requires quite an adjustment to civilian life. I am happy to be alive. All I wanted was to have life. Ideally I’d love to be 200 years old. I hope to remain a very active old man, always working so that I don’t need to rely on my children for help.

Since I was a young boy, my basic ideology has never changed. I still feel everyone should have the same rights, not just a few of the privileged. The spirit of consciencia remains alive in my deepest core.

Alfredo, Caroline (story recorder) and Alfredo’s brother Christian.

Christian’s story is recorded in embracingelsalvador.org